Home

Dec 19

2025

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Politicians often tell us that “diversity is our strength”. It sounds reassuring, but it raises an important and, in my view, rarely explored question: diversity of what, exactly? Perspectives, values, behaviours, customs, languages, ethnic backgrounds, religions – or all of the above? The answer matters, because different kinds of difference are not equally easy to weave into a socially cohesive whole. If diversity is genuinely to become a strength, leaders must articulate far more clearly to us what they mean by it and how they intend to make it work.

Some forms of diversity sit comfortably alongside one another. People from varied ethnic backgrounds may share a religion, a political outlook, or a commitment to common laws and customs. Others may hold very different beliefs yet still agree on basic civic norms. The challenge for leadership, whether of a country, community, congregation or organisation, is not simply to celebrate difference but to be clearer how a population with diverse histories, beliefs and practices can be united sufficiently to function as a stable, cooperative society. Recent surveys have suggested that Gen Z are experiencing loneliness and isolation and also that few feel proud of this country, nor would fight for it. A leader needs to provide a goal, vision and strategy that people of diverse ages and backgrounds can buy into and then inspire them to unite and go on that journey with them.

My suggestion would be to start with what we have in common. Across cultures we live in families, seek meaning, have dreams and aspirations for ourselves and others. Peace, economic stability, functioning institutions, good health and educational systems benefit us all. In an era of intense focus on multiculturalism, it is easy to lose sight of our common humanity, yet it is precisely here that social cohesion begins.

Respect for difference is often presented as a central requirement of living together, and being open to listening to alternative views is indeed essential. However, respect cannot mean the suspension of hard-won legal and moral principles. Politicians who appear willing, in the name of change or multiculturalism, to tolerate practices that undermine women’s rights, equality before the law, or protection from violence risk alienating large sections of the population. Even those who disagree with a leader politically tend to respect clarity of principle and the willingness to defend social and legal advances. After all, this is how civilisations are created – by building, generation upon generation, on what is learnt and developed over history, in the form of knowledge, science, medicine, technology, culture, music, art and wisdom.

These achievements were not inevitable and they remain fragile. Protecting them requires leaders who are prepared to state plainly that while beliefs and customs may differ, the legal framework and basic rights within a society are non-negotiable. However, many politicians appear reluctant to speak up on this. Freedom of speech itself feels increasingly constrained even for those in government, and difficult subjects are often avoided for fear of causing offence. Yet no problem can be addressed if it is not examined honestly, put under the laboratory lamp, investigated, analysed and subjected to a multitude of potential solutions. If a problem is pushed under the table and not discussed objectively it will never be solved. Open, evidence-based debate is not an act of hostility towards any group but a prerequisite for maintaining public trust. Without trust, and some sense of belonging to a land we value, we lose the sense of our shared humanity and too easily divide into factions.

In a short, myopic and complacent moment, we thought we had come to the end of history and that liberal democracy would be the future. Yet from the erosion of women’s rights in parts of the Middle East and Afghanistan, to religious violence in Africa and the rise of authoritarianism more broadly, we are reminded that we cannot take democracy for granted. The huge demographic change that has taken place in many countries over my lifetime has altered the assumptions that once underpinned everyday social interaction. The values, norms, customs, relationships and perspectives of individuals differ significantly from whether they were born in London or Delhi, Jeddah or Lagos, New York or Beijing. As the psychologist Professor Steven Pinker has observed, societies rely on a degree of shared “common knowledge” – unspoken understandings about norms, laws and customs, including humour. When those assumptions fragment, cooperation becomes harder.

It is time for political and religious leaders alike – across all faiths and none – to help us shape this evolving society. We need more leadership as to how we now think about ourselves, in order to collaborate for the good of the individual and the community as a whole. We can’t let diversity tear us apart so it is time for leaders to demonstrate, in practice and not just in rhetoric, how that strength of which they speak can be achieved. How, if we disagree about politics, theology or culture, we can still commit to a shared life in a social community, that is grounded in mutual responsibility and where the benefits of diversity are transparent and can flourish.

Diversity can be a strength when one is problem-solving. I have witnessed in jury service and in business environments, times when different perspectives, drawn together openly in a creative process, such as Edward de Bono’s Six Hat Thinking or as described in Matthew Syed’s book Rebel Ideas: The Power of Thinking Differently, can produce insightful results. However, there must be sufficient common ground and understanding to ensure that in that process people are indeed on the same side and have the same goals and intentions. This takes care, sensitivity and leadership.

To unite a whole country or community who have diverse beliefs, cultures, customs and histories a leader needs first to remind us of our common humanity, then motivate us to unite in shared goals. I have not seen this kind of leadership anywhere in the world so far. I truly hope I shall witness more of it in 2026.

Nov 19

2025

2 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Lisa Nandy suggested the other day that people were just getting on with their daily lives and not speculating about the budget. How arrogant this is and how disconnected from the fact that most people are very much concerned about the budget because it impacts their livelihoods.

The country is in paralysis, overwhelmed by the endless confusing messages coming from No.11 about the future budget. One day it’s income tax rises, the next it’s pensions, the next it’s a ‘mansion’ tax (although most ‘mansions’ in London and the South East are actually simply Victorian terraced or semi-detached houses that are far from being a mansion), the next it’s inheritance tax. Everyone is in the firing line.

These messages are generating fear and fear is the last thing people need, considering the government’s main message when they came into power was to promote growth. You can’t start a business, grow a business, or innovate if you are in fear. You need optimism. Without it no one would start any new venture.

But the attitude of Reeves and Nandy suggesting people aren’t taking notice of the budget reflects the unhealthy relationship we have to money in this country, as if money is a dirty word and those who make it become the “filthy” rich. But of course all of us are interested in how tax decisions will impact our ability to pay our bills. Wouldn’t we all like a little more money than we currently have? To pay off a mortgage? Feel secure on the rent? Take a few days’ holiday? Buy something for your child, parent or partner? Mend the leak in the roof? Most of us would.

A recent Times survey showed that almost no one feels they are rich because we all feel we are just struggling to pay our bills. The consequence is little growth because we can’t go to the shops and support the businesses on our high street, let alone other luxuries. The number of true millionaires or billionaires is miniscule – but if they, and other wealth creators, leave the country we shall be the worse off as they employ people, spend money and – which few people give them credit for – give large amounts to charity. Without those charitable donations much good work will be lost, and the State can’t afford to support the work these charities provide.

In a similar survey, the majority of people seemed to think that if you were reasonably wealthy it was down to ‘luck’. What an extraordinarily short-sighted perspective. Do people not realize how much time and effort is put into creating and running a business? If you set up your own company, however small, you spend 24/7 thinking about it, taking responsibility for the salaries and mortgages of your staff, watching competitors and the markets, and have often mortgaged your home to get it started. Whilst luck plays a part, it is the very unusual company or wealth that has been created other than through hard graft.

I think of Mark Knopfler’s song The Scaffolder’s Wife

“…don’t begrudge her the Merc

It’s been nothing but work and a hard life,

losing her looks over company books …”

Those who have gone into politics or the civil service straight from school or university have no experience of what it takes to keep a business going, to pay the bills and provide a good service. The reality is that if we chastise those who build businesses, employ people, make a success of it, then this country is going to go bust. The average salary is around £38,000 per year so if we lose those who earn more surely there is going to be very little tax to pay for the NHS or potholes, education, infrastructure, police, benefits or defending our country from hostile states.

We need aspiration. We have a major problem of several million adults out of work and high youth unemployment. To have growth we need to encourage these young people to believe that work is fulfilling, that making money and taking responsibility for your life gives you confidence and a sense of purpose. We need to encourage people to have ideas, to work hard, to put their all into work for themselves and the country. But when those who reach success are then denigrated, it puts young people off, how can it not? If we say wealth is a bad thing because “we don’t want those rich people anyway” then we are telling young people not to put their head above the parapets to try something new, to push through the challenges and make money, pay taxes but get a just reward.

We also need to recognise that not all human beings are the same and do not have the same motivations. Every country seeking growth needs to nurture that percentage of the population who have ideas, who can see a need that others haven’t seen, who can spot the way the world is going, the way science is developing or the economy is shaping up.

The history of the human race is punctuated by those people who have had a good idea and made it happen – in science, medicine, technology, manufacturing and more. We need the wealth creators, the business creators, the employers and innovators. You can bet that many of them may have had ADHD, busy minds that came up with ideas ten to the dozen. And, of course, those innovators need teams with diverse skills and temperaments to help them make it work.

We need to be encouraged to work, to save for a rainy day and save for our pensions rather than being threatened with having our savings or pension pots raided when we have done the sensible thing with our money. Businesses need to be encouraged to employ people rather than be taxed too highly or burdened with over-complicated regulation for doing so.

If those who are in power don’t understand that we have so many people in this country who have built small businesses and are working hard to make them profitable and are therefore very much preoccupied with what Rachel Reeves is saying, and is about to say, then they don’t understand their voters. These endless statements about the budget are limiting creativity and innovation, demotivating the solution-providers. We risk becoming, in Hayek’s words, “serfs” where the State takes over and our freedoms are reduced through being ground down by fear and lack of resource. It is the road to authoritarianism if we aren’t careful.

So let’s take our hats off to the scaffolder and his wife, and others who work hard and get both fulfilment and wealth from doing so because that wealth pays our taxes and funds our charities. And may Reeves, Starmer, Nandy and others respect the fact that those of us who vote do take a very real interest in the budget because it impacts our lives in fundamental ways.

Nov 10

2025

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

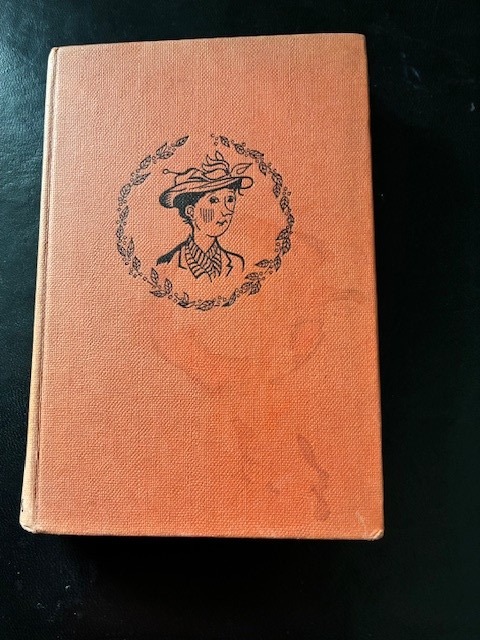

As part of The Times’ project to Get Britain Reading Andrew O’Hagan wrote a piece in last Sunday’s edition about the books that got him reading. It took my mind rolling back through the years. So many authors have come to my mind and I would love to know what books you enjoyed?

It started, of course, by being read to, but once I was reading I loved the Little Grey Rabbit stories by Alison Uttley. In fact my older sister, Sarah, and I would read them to one another every Christmas, even when we were adult. We also both adored the Mary Poppins books and Babar the Elephant. Such magic.

Then there were all those other books about animals. Yes, Peter Rabbit and Beatrix Potter but Black Beauty made such an impression and Moorland Mousie even more so. B.B was one of my favourite writers as a child and I remember having a tantrum in a bookshop in Chester when my mother wouldn’t buy me his book Mr Bumstead, about a dog. She quite sensibly refused to do it at the time of my screaming fit, but softened later and I still remember the joy of losing myself in its pages. His Wizard of Boland Forest was magical, a pre-cursor to Harry Potter maybe. My father used to read Kipling’s Just So Stories and the Greek Myths to me when he got back from the office.

Struwwelpeter by Dr Heinrich Hoffman gave me nightmares. The terrifying illustrations are referred to on the cover as “funny pictures” for little children, which I found anything but funny. Characters with huge scissors aimed to cut off the thumbs of little Suck-a-Thumb. My goodness one would have needed a few trigger warnings on that book!

C S Lewis’ Narnia books took me into all those other worlds of imagination and I remember my friends and I creating games in the woods pretending we were in Narnia. Enid Blyton taught us a lot about friendship as well as adventure and what children could get up to when there weren’t adults endlessly supervising them, as sadly has to happen these days. That freedom was heady and my generation was lucky enough to experience it, allowed to go off on bicycle rides or pony rides for hours on end with no one knowing precisely where we were or when we would return.

As teenagers in the 60s there was no such thing as ‘young adult’ or other marketing categories when I was immersed in other worlds of reading. We read adult books way before we had lived any life of our own. We knew nothing of the world, of relationships, love, lust, marriage but Pasternak and all the Russians opened up my life and I wolfed my way through War and Peace in about 3 days I loved it so much. Georgette Heyer and D K Broster also whisked me off into imagined scenes of other places and romance. Then Colette, de Beauvoir and Sartre took me to Paris and Alberto Moravia to Italy.

It was the period of the angry young men writers and I thoroughly enjoyed John Wain’s books Strike the Father Dead and The Young Visitors. Iris Murdoch was another of my favourites, always stirring up thought, and I loved Elizabeth Jane Howard’s early books.

JP Donleavy The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B is another I remember and the Tom Sharpe books had me laughing out loud on the tube.

Later in life I discovered Elizabeth von Arnim and her German Garden and more witty subtle novels.

These days I think John Boyne is one of my favourite writers and his The Heart’s Invisible Furies was both witty, poignant and insightful about other lives.

We have recently read Mother’s Milk by Edward St Aubyn for our book club and I found it a brilliant read.

All this led to me writing No Lemons in Moscow – now coming up to two years since publication! So happy to receive good reviews such as

“What a beautiful read. I couldn’t put it down! The tenderness in the ending is really special. A good insight into 1990s Russia and London. Highly recommend!”

And that make me think that my publisher would suggest it might make a good Christmas present for someone you know …?

Anyway, happy reading. I hope these memories have triggered some of your own and I would love to know the books that set your mind alight – and the books that keep you reading in the midst of this overwhelming world of distraction.

Oct 26

2025

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

As a child my Sundays were thoroughly boring. Our parents bought every newspaper there was to read and sat behind broadsheets for much of the day. It was a very visual experience as they literally disappeared behind the headlines. And yet we could sense their pleasure in this pastime, as they shared between them news or opinions about what they were reading and discussed the events of the day. A friend of my older sister’s remembers it as a scary time when my parents would expect them to have read the papers and be ready to share comments at the lunch table!

Nonetheless, my parents’ pleasure was tangible and so, as I open up my newspapers at weekends now, I think of them and take delight in sitting on the sofa with countless bits of paper around me, taking in news and opinion. I realize we are supposed to read online for environmental reasons but the problem with this is that, unlike our own childhood or that of my sons, children are not seeing what their parents are doing. The parents may well be reading the newspaper, or a book, but if it is on screen the child has no visual clue as to what the parent is looking at.

Children watch adults and learn from them. If you play music in the home they are likely to do so in their own homes. If they see you read, they are more likely to do so themselves. And so it is important that children see adults reading books and newspapers if we want them to get off their screens and into books. But what do they see around them? More-or-less every adult on a tube train is on their screen. Almost zero physical newspapers are being read in front of them and very few physical books.

It is therefore very important that parents and adults share what they are doing, talk about what they are reading, explain their interest and pleasure, or the emotions that are being stirred by it. Paint the pictures, conjure up the characters.

Graphic novels can get children and adults reading but they don’t stimulate the imagination in the way a book does. Our brains have to work quite hard – though it doesn’t feel like work – to imagine what a landscape might look like, what a character might look like, their clothes, hair, height. They have to imagine scenes, emotions, expressions, looks exchanged between characters. They also develop empathy – feel fearful for what might happen to someone, sad about a tragedy, or angry at unfairness or cruelty (I’ll never forget Black Beauty). Often then when you go to a movie of the book it does not match one’s imagination. But that’s ok because one’s imagination has already been awoken and stimulated and taken into many different worlds beyond one’s own.

Children who watch movies and TV series are stimulated and drawn into stories but the director and producer have done the creative work of imagining, taking the words off a page and bringing them to life. When we read a book, we do this for ourselves.

The Times and Sunday Times have a project on at the moment to “Get Britain Reading” and are encouraging people to volunteer to read in schools and donate books. I’ve written about the subject of reading before, back in 2017, in relation to a lack of literacy in prisoners “Reading wakes us shakes us and shapes us: which books woke you?” You can read it on that link if you choose to do so. Having recently attended both the Cheltenham Literary Festival and the Wimbledon Book Festival I have been reassured, by the huge numbers of people crowding the talks, that there are still adults reading books. Now we have to encourage the kids, teenagers and young adults to adopt it instead of scrolling.

Reading is a habit. It’s easy to lose the habit and, like any change of behaviour, can feel awkward for a period of time as you try to re-engage but then becomes easy because losing yourself in a book is exciting. But we all know how addictive scrolling on one’s mobile is and this is what children are facing. We know it as adults and must show them the way, and when I say show, I mean visually show them that we are reading a book or paper even if it is on screen, but preferably, at least occasionally, on paper. Take them to a bookshop or library, make it a fun outing. As a child, one of the favourite events of my week was to go to the public library. I can picture it now, all those years ago, the quiet, the smell of books, the feel of the pages, the little red ticket, the sound of the stamp, then the delight in returning home and losing myself in those scenes.

Here’s the poem I wrote about that memory:

Saturday at the Public Library

Entering the silence,

a stillness of concentration,

quiet shuffling of pages turning,

a scrape of chair leg,

the ‘tut’ or ‘sssh’

of tetchy adults

waiting to be disturbed.

Then the tiptoed walk

in short white socks, Start-Rite sandals,

squeaking rubber soles of embarrassment

sweaty hand on the brass-handled door

to the Children’s Section,

a never-never land of exploration

as exciting an adventure as the North Pole.

Sacrosanct hours of mind and page,

I’d settle in to touch and scent

of red, green and blue bound books,

musty paper of patchwork worlds

and transporting words.

The prize clasped carefully,

anticipation heightened by the thud of the date stamp.

Today’s libraries open to a different quiet:

a bright screen, door to the world,

feasts of libraries, blogs, museums, news,

too much to take in or digest.

A few books hold on to their shelves

but paper becomes obsolete in the cold world

of a tapping keyboard.

Let’s hold onto the magic of books we hold in our hands as well as being awe-inspired by what our tapping keyboard can bring. We don’t have to lose one for the addictive demands of the other. We can enjoy both – and talk about it.

Oct 14

2025

9 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Every day on the tube, in cafés and shops, I bump into young girls and women with false eyelashes, pumped up cheeks and pouty lips. They are buying creams and moisturisers at an age at which I wasn’t giving any thought to my appearance or skincare. I was just enjoying my childhood. I read that huge amounts of money are being spent now on tweaking and Botox and filling and I feel sad that so much attention is being paid to the outer appearance when what really matters is what lies within, what is in a person’s heart and mind. What used to be referred to as character.

We all care what we look like as we move from our teens to adulthood. Consciously or unconsciously, we are trying to demonstrate something about ourselves, what our little tribe of friends enjoys and stands for. What we wear defines us to some extent and can give us a sense of belonging. The fact that, growing up in the 1950s and 60s, we wore too much make-up or mascara and wore skirts shorter than our parents approved of was a passing trend and did not impact our physical body in any long-lasting way. We could wipe off the mascara, buy new clothes. But when young girls and women today are using physical interventions such as Botox this potentially has a much more lasting impact, as does the trend for tattoos, which I have personally never been able to understand. Facelifts often require further work later in life. How will all this look as they age? And what is it that is making young women so unaccepting of who they are? To me, as I observe all this, their skin is so fresh and beautiful I just wish they could relax and appreciate it!

Which reminds me of a time years ago when I was on the beach with one of my son’s girl friends and she was fretting about her beautiful young body not being good enough. It reminded me of the fact that I had also constantly felt discontent with my appearance and I pointed out to her that she might as well appreciate what she had today, with all its (in my mind non-existent) blemishes, because tomorrow it would be older and then she would have more wear-and-tear, children, perhaps, and might lose that blossom that young girls can have. Value what you have now, was my message, and I remind myself of this frequently now I am 75, to appreciate every functioning aspect of this miracle that is our body, for whatever is working today may well not do so tomorrow!

Fashions change and it is fun to keep up, albeit quite challenging. Hair in the 50s was wavy, in the 60s was Vidal Sassoon’s flat as a pancake style. This was hopeless for those of us with natural curls when there were no blow driers. I tried sellotaping or ironing out the curls, sadly without much success! However, hair grows back and so if we have an awful cut one day we can relax that in a month or so we will return to normal. We did have a short phase of wearing false eyelashes when I was about 18 but they were not of a good design and would get left on the shoulders of a boyfriend if we were dancing too close. Not a good look to have one set of eyelashes long and one set short! The eyelashes that are in fashion now are patently not trying to look natural, but these can be removed and will not necessarily have any lasting impact.

There was a rebellion against make-up in the 1980s and 90s when feminists argued that we should not need to wear make up at all, should not need to shave or make an effort, for all that mattered was who we were within. Well, yes, that argument is a strong one and I go along with it as, ultimately, relationships are about who we are as people rather than what we look like. You can be beautiful but mean, handsome but selfish. How we are and how we respond and treat others is the key. And yet our appearance does matter even if just because we have to look at ourselves in the mirror and want to feel confident enough to face the world.

For some decades I thought that we had achieved being taken for our skills, personal qualities and talents and not our looks when it came to our careers or relationships. But all of a sudden, we seem to have gone backwards – to young girls fixating on their skin, the focus being on outward appearance rather than inner beauty, knowledge or wisdom. I’m not sure what is driving this, other than some influencers who are presumably being paid large amounts of money to promote certain products. Who is it for? I have made the mistake of trying to adapt to one partner who said I needed to lose weight followed by another who found me too thin for his taste. I learnt that you can’t please everyone, so it helps to accept what we have been given in life, and yes make the most of it but not obsess about how we look. Yet this trend is influencing boys and men too, as they pump up their muscles at the gym and I presume that this is also being driven by influencers and celebrity role models.

Where are the role models who promote the fact that you gain confidence by valuing who you are not just what you look like? The work to be done is, in my humble experience, usually on the inside. Reflecting on values, beliefs, behaviours, setting goals about who you are and what you want to become, and understanding that this process does not stop aged 18, when you think you have become ‘adult’, but in fact is a lifelong journey of inner reflection on who you want to be in the ever-changing world in which you live.

I still wish my hair was straighter, that perhaps I was a little lighter but it’s what happens on the inside that shapes the experience of my day. Am I happy with the knowledge I have, with the skills I have developed? Is there something else I could learn or an aspect of my mind or personality I could develop further? Am I being the person I want to be, speaking up for the things I care about, treating people with respect, giving time to those I love?

Too many of the Gen Z influencers that I have come across are promoting all the problems of our time whilst others are promoting beauty products. Can I please put in a plea for someone to help young people to spend more time developing inner wisdom (what they are learning about life), academic knowledge, work skills and personal confidence and less on sticking on false eyelashes or pumping up huge biceps?

Sep 29

2025

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I think everyone knows that the phrase “don’t think of an elephant” leads to pretty much everyone thinking, and even picturing, an elephant. What you focus on gets reinforced.

This week Baroness Spielman, the former head of Ofsted, has expressed concern that schools are becoming centres of therapy and yet are not trained to be so. Their main qualifications and purpose are in educating children in the academic curriculum. Despite this, many teachers are being encouraged to provide trigger warnings and even ban certain books, including, it seems, some of Shakespeare’s plays, The Great Gatsby, Charlotte’s Web (apparently because there is talk of death and also talking animals), Matilda, and my favourite book as a child The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. You can find offence anywhere if you look for it.

The problem is that the more you train a young mind to look for offence, for problems, for bias, the more that brain will build the habit of seeking out and noticing the negatives and not the positives. Governments are talking about building resilience in young people, but their actions are in danger of disempowering them rather than empowering them.

As Spielman has pointed out, teachers now not only highlight potential problem areas in books which most previous generations have read without trauma but also ask children to talk about their negative emotions. If this is the case then I sincerely hope that they also focus a child’s attention on their helpful emotions too, and on what the child can appreciate and be grateful for. Otherwise we shall certainly be raising a generation whose minds have been trained only to see the negatives, not the opportunities or the creative possibilities, but potentially training them for victimhood, which doesn’t help them and certainly doesn’t help society.

Ok, so previous generations may have been too much ‘stiff upper lip’ but I suspect that if you were living in a brutal world, as life has been for centuries, a world of war, disease, small children dying for lack of vaccines or antibiotics, mothers dying in childbirth, fathers in war, people needed to focus on how to make each day good, for life was short and food and resources scarce. That probably resulted in a need to just get on with things.

Although there is much talk of how terrible life is today, the reality is that we are healthier, living longer, more accepting of all kinds of diversity and communicating across the globe in ways our forefathers never did or could. Yes, there are threats but let’s not overlook the advances or the peace that we have enjoyed.

We have indeed gained benefit from psychology and a deeper understanding of some mental health conditions but I don’t believe that we necessarily need to treat everyone as vulnerable. Otherwise, as I have said above, we all turn into fragile beings, unable to cope with life’s everyday challenges, let alone the kind of challenges our grandparents had to face, or we might have to face in future.

For expectations have outcomes. What we expect of ourselves, and others, transmits a message through voice tone and body language as well as words. There is research that has shown that a teacher’s expectations of a child shapes that child’s results – expect them to be clever, they become clever; expect them to be stupid, they become stupid.

We therefore need to give the message that the majority of us are competent and capable human beings, not that we are all fragile and vulnerable creatures who can’t manage life. The welfare state is designed for those who really need it, but they will be deprived of essential support if funds are dissipated on many more who, through kind intention no doubt, have been led to believe that they can’t cope. Witness the huge increase in children seeking mental health support.

It seems to me that recently educators and governments have been focusing young people’s minds too much on the negatives – the likelihood of victimhood, the likelihood of bias or being upset or offended by something. Trigger warnings on everything they watch or read just emphasizes the idea that they are under threat, even if they aren’t. And whether they are under threat or not we need to help them feel empowered to deal with life.

The trouble with trigger warnings is that they alert a child’s amygdala (the part of the brain in charge of fight or flight responses) to the fact that there is a potential threat, even if that threat is thoroughly unlikely or nebulous. As I explain in Cognitive-Behavioural Coaching Techniques for Dummies you become familiar with the way that the brain builds habits and patterns of thoughts and reactions. If someone is disempowered it is likely that they are being driven by underlying Negative Automatic Thoughts. These are neural pathways of thought in the brain and can become beliefs which influence emotions and behaviours. A thought such as “I can’t cope” will increase anxiety and the child is far less likely to be able to face the situation. Instead the child can become aware of how their thoughts are disempowering them and build new thoughts such as

“I accept that I am a little nervous about this but I shall give it my best go.”

“I would rather this person didn’t behave this way but I will find ways to manage it even if they do.”

“I will treat others with respect and they are more likely to treat me with respect.”

Gradually, with repetition, the optimistic and empowering thoughts become automatic habit and their emotions and behaviours can change within this process. Think stressful thoughts and the body emits cortisol; think positive thoughts and it can emit endorphins.

I sincerely hope that governments and educators alike start to treat children and the adult population with the expectation that the majority of us are competent and resilient human beings because I believe that will translate into positive actions in society. That way the welfare funds will go to those who really need them.