Home

Aug 07

2019

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

If you are experiencing persisting physical symptoms such as stomach cramps, severe fatigue, exhaustion, pain in your muscles, over a period of several months, it is likely that you will go to your doctor in the expectation that they will be able to diagnose your problem and prescribe treatment to alleviate your symptoms. Should they tell you at the end of your appointments and investigations that they can find nothing physically wrong with you this can be bewildering and disheartening. It can be equally confusing for the doctor, who is trained to diagnose and prescribe and may well feel frustrated that he or she cannot help you.

GPs estimate that approximately 50% of patients in their waiting rooms do not have a fixed pathology of disease that they can detect. So what is happening?

Over the past five years my partner Dr David Beales, who was a GP himself for some 30 years, brought together a team of experts to research and seek solutions. We called ourselves the Reclaim Health team and the outcome of this collaboration is our book Reclaim Health: a recovery strategy when doctors can’t explain your symptoms, just published on Amazon. Click this link .

This book is for those who have or are experiencing these medically unexplained symptoms. In writing this, we have benefited hugely from having two expert ex-patients in our team, Julia MacDonald and Janice Benning, both of whom were severely unwell for more than 10 years with chronic fatigue syndrome. They used the tools and strategies in this book to reclaim their own health and have since then applied this process to many clients, with excellent results. Janice and Julia were able not only to provide us with their experiences but also help us to present our findings, tips and techniques in this book in a simple yet powerful way, knowing that when you are unwell you do not have much energy to read, let alone read anything complicated.

We initially approached this as a research project, obtaining funds from the National Institute of Health to research the literature and Janice and Julia then ran a pilot course to test recovery techniques, which we accomplished. One of the keys to success is to give an empowering explanation of the symptoms a patient is experiencing, within the context of their immune system. For more information on this please click to see David’s article.

The two GPs in the team, David and Gina Johnson, have added the science and their practical experience of working with these patients, addressing how the interconnection between mind and body can influence symptoms. I have contributed the coaching processes that can help a patient pursue their goals of wellbeing and return to their lives as healthy individuals, breaking through old patterns and persisting through everyday challenges.

I suspect that any of you reading this may either have experienced these symptoms yourself or know someone who may be struggling to reclaim their health. Do take a look at it on Amazon and buy a copy or send one to a friend you think may benefit. As a not-for-profit team, we have kept the price intentionally low, at cost, £4.83 so that as many people as possible will be able to take advantage of the experiences, science and helpful techniques included in this book.

As a client has commented: “I use my Reclaim skills all the time, and life is good. Forever grateful.” Others can benefit too – both those with symptoms and those medics, coaches, therapists, HR teams, or family and friends who are supporting someone who is suffering from problems such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, Irritable Bowel.

It is such a shame to feel so debilitated that you can’t participate or enjoy life. People arrive at this place for many different reasons when their level of tolerance – physical, mental, spiritual – is exhausted. Sometimes people feel so unwell that they can’t enjoy their partner, children, work or even the hobbies they used to love. But as with anything in life this can lead to habits, conscious or unconscious, that keep you stuck and then returning to health and life can seem scary, like too big a challenge. The task can look too steep and so people end up feeling helpless and hopeless.

But it doesn’t have to be an exhausting challenge. Gradually, small step by small step, people begin to take control of their lives again – their thoughts, emotions, physical strength, flexibility and energy. They notice when they are ‘doing’ negativity or pessimism. They begin to develop the ability to say ‘no’ to people they have found ask too much of them. They begin to tune into their bodies and recognise when they need to rest or sleep, when and what they need to eat, what exercise re-energises them, or when they just need to be still, perhaps to meditate or reflect. They begin to define the lifestyle, relationships and environmental choices that nurture them, the creativity that inspires them and to regain a sense of purpose and meaning. And key to all of this is compassion – compassion for self and compassion for others.

Sadly many people are told that they will never recover from these kinds of chronic and debilitating conditions. We would like to encourage them to believe that they can – and include plenty of case studies in the book of those who have turned their lives around to reclaim their health. So I shall just finish with one example of a client in his 20s, Edward, who gave this feedback after sessions with Janice:

“I thought my life was over, but 2 years later I have climbed Snowdon and celebrated with a pint! I wouldn’t have the energy to watch a park run, but now I run it. Knowing there was another way that would allow me to live my life was the most liberating and emotional experience.”

We believe that this book provides that help so do click here to take a peek at it and let us know how you, or anyone you know who reads it, gets on! Do visit our website www.reclaimhealth.org.uk. We would love your feedback.

Jul 02

2019

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Do you know what Hazing is? I certainly didn’t until very recently and am horrified to discover that it is happening in this country, at our universities. For those of you who don’t know, it involves initiation practices that have come over here from the States, I believe. It includes revolting, humiliating and sometimes painful rituals to initiate new students into a group, rugby club, university or college. I have heard about people having a chilli put up their rectum, a young girl blindfolded and taken into the countryside and left in a wood to find her way home, apple bobbing to fish dead rats from buckets with their mouths, people being forced to drink excessive quantities of alcohol. It is a dangerous horrible practice and it seems that it is happening at a university near you without us oldies realizing it. Do we want this for our grandchildren?

It made me aware of how many dubious behaviours are occurring here without me knowing. It makes me feel left behind, out of touch and anxious to spread awareness, as surely we should be fighting to stop any kind of humiliating ritual, whatever its cultural provenance, from happening here. Isn’t this contrary to any kind of human dignity or protection of human rights?

But the only way I really hear about what’s happening is via younger people, whether they be nephews or nieces, sons or daughters, so I suspect that many people are blissfully unaware of some of the practices that I consider abhorrent and would like to challenge. Here are a few examples, as well as the Hazing examples I gave above…

Breast ironing. This is only just coming to light but social workers and doctors must have known about this practice for some time without publicising it. The British Medical Journal, 4 May 2019, carried an article reporting that some 1000 women and girls in the UK may have been subjected to what can only be described as abuse. For those of you who have not heard of this practice it is breast flattening, where a young girl’s breasts are ironed, massaged, flattened, or pounded down to reduce their size, supposedly to protect girls from sexual attention and delay sexual development. It is common to some parts of Africa and the Cameroon. This is described by the UN as gender-based violence and causes significant harm. No perpetrators have yet been prosecuted in the UK and it seems that there is general ignorance of a repugnant practice that amounts to child abuse. How can we prevent it if we don’t know about it?

Female Genital Mutilation. We do now have more information and awareness of this practice and yet there has only been one prosecution. As with other practices there seems to be a veil of silence being held by people who must surely know where it is happening and who is perpetrating it?

Boys and porn. It seems that people take it for granted that young boys will have access to porn these days but how have we allowed this to be so easily available? As with the above behaviours, it introduces expectations of young girls to perform and live up to the habits of porn stars. One of these is to shave off all their pubic hair, which is apparently now commonly done by teenage girls in this country. Why? It seems to suggest that girls are being infantalised for the pleasure of boys and men. It suggests that the ability to take pride in being a natural woman is being removed from them.

Young wives being used to produce children and then divorced and deprived of seeing their children. This is hideously cruel but apparently is carried out by British husband who send their wives away to Pakistan and other countries once they have produced children. This practice was reported as long ago by 2012 by the BBC but is still happening. Does this require education, or a legal change to protect mothers and ensure they can see their children after divorce?

The Black Web. I hear about this but I haven’t a clue what it really is or how on earth to access it (not that I would wish to). It’s a bit like a black hole – it exists but doesn’t exist for most of us and heaven knows what unpleasant things are being shared on it but is there no way to stop people accessing it, if it is showing illegal material?

Cutting and self-harming. This didn’t really seem to exist in my school days, certainly not in the numbers that are now being reported. How sad. But we must remember that teenagers are groupies, they do what other members of their friendship group do and so it is a practice that becomes infectious, as does anxiety. And in some ways the more we publicise it the more we fan the fire, don’t we? It is excellent that we understand that it is happening, certainly, as we can then support those who are undertaking this harmful practice and understand what is leading them to do so. However, it strikes me that the more the media blow it up the more likely it is for a young girl to feel the odd one out if she isn’t self-harming or suffering from anxiety these days. My experience is that we were all anxious as teenagers – there is so much ahead that is uncertain – but we accepted that it was just part of life, a stage we had to go through until we gained a little more control. Of course we must support those who are mentally sick but perhaps not over-pathologise those who are experiencing the usual teenage angst? But perhaps if I was subjected to some of the changes above I might have become equally anxious.

Social media versus newspapers. Yes, we all know about it but what I didn’t know until recently was that young people are getting all their news from Instagram or Twitter. They aren’t reading newspapers. And this means that they aren’t reading comment or analysis, they are just reading headlines and getting snapshots of information rather than any kind of broad or in-depth information with which to make decisions or form informed opinions. And then they vote and have our future in their hands.

I remember Sundays as the most boring day in the week in my childhood home as my parents tucked themselves behind The Times, Observer, Telegraph and read them from cover to cover. Whilst I was bored it nonetheless gave me a role model that this was something adults enjoyed doing – getting information about the world, discussing it, debating views, etc. And so we children of our era learnt that newspapers were interesting things to read and have around. I have followed suit and always had newspapers and journals strewn around the house so my sons have probably experienced equal boredom to my own.

The thing with physical papers is that one sees more than one ever does on line – the odd little paragraph in a corner of a page, an article one might not have considered to be interesting but proves fascinating. I find that online one misses a lot as much of it is reliant on one’s searching for articles rather than that randomness of glancing across a page or two and seeing something that catches the eye. And then of course papers like the Standard are even shedding the experienced critics who inform us of their opinion of books, theatre, film, etc. so that one gets the views of any old Tom, Dick, Harry or Henrietta who may or may not have any real knowledge of the subject at all.

And so here I am feeling left behind, as I am sure most older people have done in every generation, as all kinds of new habits and practices infiltrate one’s life and society. But some of these behaviours seem thoroughly disrespectful to humanity, and to women and girls in particular, so surely we need to know about them in order to challenge them? What do you think, I wonder?

Jun 18

2019

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

Words like bigot, Nazi, fascist are being bandied about at rapid speed these days with little understanding of the real meaning of the words or their sorry history. Nor does there seem to be a recognition that the person accusing others of bigotry might actually be as much, if not more, of a bigot than the people to whom they are addressing their accusation.

Bigot means a person who is intolerant towards those holding different opinions and today it is used by those who often want to prevent others expressing their opinions. This may be student unions who no-platform lecturers or academics who do not hold their views. It may be those who express an opinion on race, immigration or culture who are not allowed to have concerns that may well be legitimate. It may be either Remainers or Brexiteers who are unwilling to listen to the arguments of those whose opinions differ to their own. It may be those who express concern about the stance of the transgender lobby. It may be Trump-haters or supporters, Tory-haters or supporters, and so on.

We are not living under a communist regime. We do not have the Stasi or other secret police patrolling our streets for dissidents… yet! The word Nazi has an altogether more sinister meaning, with all its inherent anti-semitism and fascist authoritarianism. Surely these are inaccurate descriptions of someone who happens to holds differing views to someone else on the topics raised above. But using them raises the emotional atmosphere, conjuring up death camps and dictatorship. It’s a shaming exercise.

And it can well be the supposedly ‘liberal’ person who is throwing these criticisms in other people’s direction. It seems to me that we are living in a very illiberal, but supposedly liberal, society where unless you hold the ‘woke’ view you are labelled a bigot, Nazi or fascist. This is loose language. And who, really, is the bigot in such cases? Surely someone with views on immigration, Brexit, gender or other topics has the right to be heard? Surely the person who dismisses other people’s views out of hand is equally a bigot? Surely a more constructive way to pull other people’s views into one’s own direction is to hear their concerns, their rationale and try to understand their point of view? Silencing people only stimulates anger, resentment and division.

Recently Julie Bindel, founder of Justice for Women, was attacked and called a Nazi after she gave a talk at Edinburgh University on women’s sex-based rights. She lectures on her concerns about gender identity being accepted on the basis of self-definition alone. This policy is resulting in male-bodied ‘women’ having the right to enter women’s changing rooms, women’s prisons and toilets. For these views she is labelled a bigot, Nazi and transphobe for her legitimate questions about how female a male with a penis identifying as a woman really is and how much of a threat they might pose.

Who is the bigot here? Julie Bindel for expressing her disquiet that these policies are becoming practice despite no national debate or legal basis? Or the person who tries to get her no-platformed? Who is the bigot when someone living in an area of high immigration expresses their concern at feeling a stranger in their own country, at the cultural and social implications to themselves and their families, but is told flatly that they are a racist, fascist, Nazi? Bigotry is silencing those with whom someone disagrees. And we are witnessing far too much of it at the moment.

No doubt I would be labelled a bigot for having concerns myself when I went to the theatre last night and the sign on the Ladies welcomed people of any gender-identity entering the area. I confess to being disturbed about men with penises who decide they want to identify as a woman entering my changing room or toilets. We know that male on female violence and sexual harassment is statistically far higher than vice-versa and so these areas that were safe spaces for women no longer feel so safe.

There is a time in every child’s life when a parent allows them to go to the lavatory or into a changing room on their own. It is a part of their journey to independence. But I confess that as a mother or grandmother, I would feel far more hesitant to allow a young girl to go into these areas alone if I knew a man might be there changing or doing his business.

There are intimate things a young girl has to learn – managing periods, how to insert a tampax or lillet. I remember this wasn’t as easy as it sounded when I was 13! These are sensitive issues for women, issues that men identifying as women do not have to deal with. And call me old-fashioned but men tend not to worry so much about care and hygiene as they don’t always have to sit on a seat. I remember for myself, and know with my granddaughters, that many girls do care about these things. How can it be that girls and women are just supposed to put up with this change to their private spaces without any proper debate or discussion? Instead, anyone who raises the matter is labelled a transphobe or bigot despite the fact that those people are often compassionate and tolerant of those who have gender issues. Can there not be a third way?

People are denigrated for being binary thinkers about gender and yet those with whom I have discussed the transgender issues end up equally binary – a man wanting to be a woman or a woman wanting to be a man. So who is the confused one? If there is a third or other category that people wish to be known as then so be it but I am sorry, for me otherwise biology wins. A woman with womb and ovaries is not a man, a man with a penis is not a woman. They can wear what they like and consider themselves as whichever sex they prefer, but please don’t just call yourself a woman and enter a young girl’s private space without agreement. I worry that the trans lobby is actually turning the clocks back on the rights women have won in the last fifty years.

I worry (a lot of worries here I notice!) also about how Mermaids and Stonewall are lobbying for sex change treatment in children far too young to know what their future will be like, whether they are a man, woman or trans. A young child can have no real knowledge of gender, sex or relationships

What I don’t understand is that millenials are demanding safe spaces everywhere – in universities, to be warned that they are about to read a disturbing fact in a history book, or even in Shakespeare, for others not to appropriate their experience or culture, etc. And yet when it comes to transgender they go along with the current thinking that girls and women don’t have to have safe spaces. I don’t get it. Women are once again being silenced and then being called a fascist, Nazi or bigot if they protest. Again, who is the bigot?

In sport men who have had all the benefits of testosterone, the bone and muscle formation of a man, quite apart from all the cultural messages men receive, decide they are a woman and want to compete against women whose bodies are formed in a completely different way. To me this doesn’t seem fair but anyone who complains is called a transphobe. I have just been reading Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez which covers the historic legacy of how women have been written out of a multitude of situations. I don’t wish to witness women’s needs once again being eradicated in the name of a supposedly liberal movement that is far from liberal.

I worry greatly at this intolerance of language and debate. You learn far more from standing in other people’s shoes, seeking to understand their issues and evidence. The Socratic and Aristotelian method was to argue from the opposite perspective. This broadens your mind, sharpens your thinking and has a greater likelihood of taking all opinions into account in final decision-making. This would apply as much to Brexit, Trump, Corbyn, far-right or far-left policies, gender, immigration and more. It is a debating process that would be beneficial to introduce into schools so that people stop making their minds up from very little information, stop shouting abuse at others before they have understood where they are coming from, and genuinely try to understand one another.

Again, call me old-fashioned… and is that such a bad thing? … but respect for others and their opinions, polite and calm discussion, can help us all understand one another better. As Jonathan Haidt argues in his excellent book The Righteous Mind, good people have different opinions to our own but we should not label them evil, Nazi, fascist or bigot unless we are very sure of our facts and very sure that it is not us who is being the bigot.

May 20

2019

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

There’s a theme of disillusionment with politicians and leaders today. A movement to eject current leaders with the concept that there may be someone better, a greener grass, beyond. However, as I look around the world I am not convinced by the alternatives we have on offer at the moment and worry that it is easy to get rid of a mediocre Prime Minister or a deranged President but not so easy to be sure that their replacement will be any better.

Ukraine is about to authorise a comedian to be their Prime Minister. The 5 Star movement in Italy was founded by Beppe Grillo, another comedian. The danger here is naivete and inexperience, which can lead to that person being manipulated by forces they don’t understand. With key countries such as Ukraine this presents a real danger as President Putin is a world-class strategist who still has his eye on Ukraine.

When we look at the Arab Spring, Egypt, Syria and beyond, there was a successful movement to replace the old brigade but far too little thought put into who would replace them. And this can lead to anarchy, as we have seen in Libya, which often can be worse than what came before, the rule of law breaks down, infrastructure disintegrates and economic depression is an almost inevitable consequence. One needs to be clear about a vision of the future.

Division provides an impetus towards potential revolution – the gilet jaunes protesting against the elite, is an example. In fact the movement against the elite is often a signal that a revolution is in the air – lawyers, writers, academics begin to be pilloried and eventually interned. Erdogan has been doing this with surprisingly little kick-back from our press or the EU. Even in the UK there is a sense of anti-elitism in the air and also a limiting of free speech, as is evidenced by the no-platforming of lectures and events which somehow do not fit into the politically correct zeitgeist.

The criticism of the middle classes is another signal of revolution. The centre ground gets lost, the extremes come to power. But to the detriment of stability and balance. The middle classes are almost always the backbone of a country quietly getting on with life. On the whole they have more to lose. They tend to value education, aspiration, economic stability, peace, low crime rates in the areas in which they live. You tend to find them as councillors, volunteers and on parent school boards. You find them running small businesses and right now that squeezed middle is not only under some financial constraint but also under attack from the press who tend to ridicule those aspirations, or from those who envy that lifestyle, however justly gained. People tend only to see the economy in terms of the big powerful organisations at whom they love to throw stones. They too easily forget that some 99% of businesses in the UK are SMEs – small entrepreneurial enterprises employing only a small number of people.

Revolutions are bloody. Surely to be avoided if evolutional change can be achieved. And the problem with the way our own political landscape appears at the moment is that we have factions and no-one is in the centre ground. People promote the Lib Dems as the party holding the centre but by naming their stand as “Bollocks to Brexit” they have as effectively put two fingers up to the Leavers as the dreadful Farage has done to the Remainers with his Brexit party. Both are divisive. Neither give any hint, as far as I can see, of what they will do to bring the country back together again or to take care of the concerns of those who stand for opposing views. Both the Labour and Conservative parties are too divided within themselves to lead a united country. So what next… there lies the void. There lies the danger. It is into this absence that oddball narcissists such as Farage or Johnson can slide.

I have been amazed by how little in-depth debate there has been about the future of the EU or the future of the UK after whatever deal is or isn’t done. We have heard endlessly from Laura Kuenssberg and Katya Adler on the BBC commenting narrowly on the Brexit negotiations. We need new viewpoints, new perspectives.

We haven’t heard enough, in my view, about the build up to the European elections within other EU countries, the challenges, policies and strategies that are being discussed in other capital cities. The mood of the people in these countries. What is happening in Bulgaria, Romania, Lithuania, Croatia? We hear endlessly about Macron and Merkel but not enough information about the other 25 countries. Yet this information is key to how we think about ourselves in the UK in terms of our future relationship with the EU. We haven’t heard enough about how any government will address the perfectly legitimate concerns of the losing party here, whether this is the Remainers or the Leavers. We haven’t heard enough about how any government will mend the bridges that have been broken here or what they will do to maintain relationships with our close or distant allies. The conversation and comment has been far too narrow. I feel I still have far more questions than answers. I am happy for anyone to provide me with more information …

And this leaves a leadership gap because we aren’t being given an accurate or desirable picture of a future that we can agree on. I look at the options we have for leaders in the UK and am not convinced by any of them, unfortunately. We don’t want a ‘strong man’ as they can tend to turn into egotistical dictators but we do want someone who listens to the concerns of the whole country and has a practical vision of how to take us forward in a united way. I just don’t see this person evident at the moment… do any of you?

May 07

2019

4 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I have to admit to being fed up with being accused of “stealing” the younger generation’s future. The word stealing implies intention to cause harm to another person, to deliberately deprive them of something that is theirs. I don’t buy into the concept that my generation of Baby Boomers, who seem to be the target of any blame game that is going at the moment, intentionally stole anyone’s future. Nor do I think we are necessarily any more selfish than any other generation – lucky, yes, that we have not had a war on our territory during our lifetime but we have had our own struggles nonetheless.

We are living in an era where it’s the norm to look for others to blame for anything that is causing pain or discomfort. I don’t find this useful. Identifying yourself as a victim is disempowering and ultimately unhelpful. It makes others into persecutors – often a subjective labelling that also removes responsibility from those who consider themselves victims by ignoring the part they may themselves have played within a situation.

At the present time we Baby Boomers are being blamed for, in The Guardian’s words of 27.7.11, creating an “environmental mess”. The Extinction Revolution protests accused us of “stealing their future” by treating the planet the way we have. I really wonder how they can declare that they would have treated it better given the knowledge and circumstances we were born into? It is easy to look back through the lens of today’s world and say people did things wrong. They cannot honestly say they would have done any differently because they just don’t know how they would have acted had they been born, like I was, in 1950.

We are a species who learns through invention, experimentation and review. There was a time when if you fell into the River Thames you would have died from pollution. Today fish swim in it because we learnt not to treat it as a sewer. In 1974 F Sherwood Rowland discovered that CFS aerosol spray was causing the ozone layer to diminish. Action was taken to restrict the use of these aerosol cans. Predictions are that the ozone layer should have healed by the 2030s due to this change. We moved from petrol to unleaded and then to diesel because we were informed that it was better for the environment. That was erroneous and so now we move back to unleaded or renewable/electric fuel for our vehicles. We continually learn from science and change our behaviour. We don’t yet know whether the changes we have been making on behalf of the planet will overturn the damage done but habits are changing.

As so much criticism is being thrown our way I want to remind Baby Boomer readers and perhaps enlighten younger readers that not everything we did in our lifetime caused things to get worse. We were a generation whose teenage years were overshadowed by the fear of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis and we certainly protested and went on CND marches to protect the planet from nuclear holocaust. We marched against Apartheid and refused to visit or buy produce from South Africa, as well as standing up against many other iniquities.

We didn’t, as the younger generation do, have stag parties in some far flung part of the world. We went down to the local pub. Hen parties didn’t exist. We had no concept (and still don’t!) of single-wear clothing due to not being able to be seen in the same clothes twice on social media. We frequently made our own clothes and often wore them until they fell apart. The idea of buying an item of clothing only to wear once (other than perhaps a wedding dress) seems criminal to me and an appalling waste.

In the main we didn’t fly as young people. We went by ferry, train or car as aeroplane travel was hideously expensive, unreliable and with few routes. It was only when Clarksons, Freddie Laker then Easyjet and Ryan Air came on the scene that it opened the skies to the masses. And there has been some benefit from that in that more people have integrated with other cultures and broadened their minds through travel. Did we have fun? Yes of course we did and took advantage of new inventions and opportunities. Any generation would. We did not, at that time, understand the impact on the climate of air travel but today’s engines are far less polluting than the original jet engines were and so, again, we are learning. There was no intentional “Let’s go ruin the planet for our children!” We happen to love our children, grandchildren, great nieces and nephews and beyond. Why would we have done this deliberately?

The property prices are another accusation thrown at us and again I would like to remind people that many of us lived in thoroughly damp, grotty flats (in my case with condensation that fell from the ceiling and snails that crawled up the walls) which we shared with 4-6 strangers, sometimes happily sometimes not. But that was what we could afford. We then bought wrecks that we did up. Houses that needed rewiring, central heating and a complete overhaul and did much of this ourselves, living in a building site for one to two years with the long-term vision of having a decent house to live in. Which we created. As more people wanted to visit London and as more women worked, property prices went up and I am sorry that this has made it so difficult for the young to buy or live in central areas. But let’s not forget that it impacted our ability to buy ‘up’ as our families grew and that interest rates were 17% at times, with no credit cards to fall back on. So it wasn’t all plain sailing.

We came into a country that desperately needed rebuilding after the war. My memories are of bomb sites, very basic housing and economic challenge. Through the 60s, as we became teenage and young adults, we railed against the Establishment on behalf of those who wanted a more class-less and equal society. The music industry opened up wealth to a large number of people who would never have had it, as did sport. In business, people from all spheres came into white collar jobs. Many of our generation built businesses from scratch and employed thousands of people. Some of this built on Victorian industrialisation but much of it was new innovation, resulting in many of the technical and medical advances that current generations enjoy today. People worked hard. They didn’t expect that wealth or success would come unless they made it for themselves. Doctors worked around 120 hours a week. Many professionals worked well over 60. We jut got on with it.

As many statistics have proven, global poverty has reduced over these decades as office jobs have provided incomes for many people worldwide. People trying to overthrow capitalism do so at the peril of many people whose livelihoods depend on it and whose living standards have improved because of it. Of course there are excesses that need to be tempered, as there have been in any generation and in any area of the world (look at the wealth and selfishness of dictators of poor countries through the ages). Strong, greedy and selfish leaders have existed throughout history and well before industrialisation or capitalism.

Our generation have fought for gay rights, women’s rights, racial equality, flexible working, equal pay, disabled access. We haven’t got it all right – of course not – but many people have tried to create a fairer world. The hippies of the 60s and 70s were for love not war, for the organic ‘Good Life’ of growing your own vegetables and setting up organic farms. Friends of the Earth was established in 1969. The Clean Air Act was first passed in 1956. The first “Earth Day” was 1970. Amnesty was founded in 1961, Greenpeace in 1971. We haven’t been deaf or blind to environmental or humanitarian issues.

Much of what has gone wrong in terms of pollution is through individual thoughtless behaviour such as chucking litter along a road or into the sea or river. The world’s oceans and beaches have been littered with plastic bottles and cans for decades. Some of it from individual action and some of it dumped by business or governments. There needs to be far more focus on teaching children individual responsibility at school so that they don’t drop litter and they do become active participants in the global community. Then when they do get into responsible positions they will hopefully make decisions that maintain a healthy world.

There has certainly been a failure of global leadership on the environment during the past decades. I don’t understand why it hasn’t been obligatory for all new homes to have solar panels. Nor do I understand why supposedly ecologically-friendly products are still offered in plastic bottles. We have a long way to go and hopefully all generations can work together to take care of our planet.

But I don’t appreciate having one generation telling ours that we have stolen a future that is also my children’s and grandchildren’s future. Those school strikers who speak in this way haven’t entered the adult world yet and they will find it’s a more complex business than they might imagine, where many well-intentioned supposedly environmentally-friendly policies actually prove to have negative unintended consequences. So it’s easier to point fingers than it is to get it right. We didn’t get it all right but I would be surprised if any of us went out there with the deliberate intention of “Let’s ruin the planet” for future generations!

Inter-generational division is counter-productive. Let’s stop this blame game and work together to support action that will protect our natural world.

Apr 28

2019

4 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

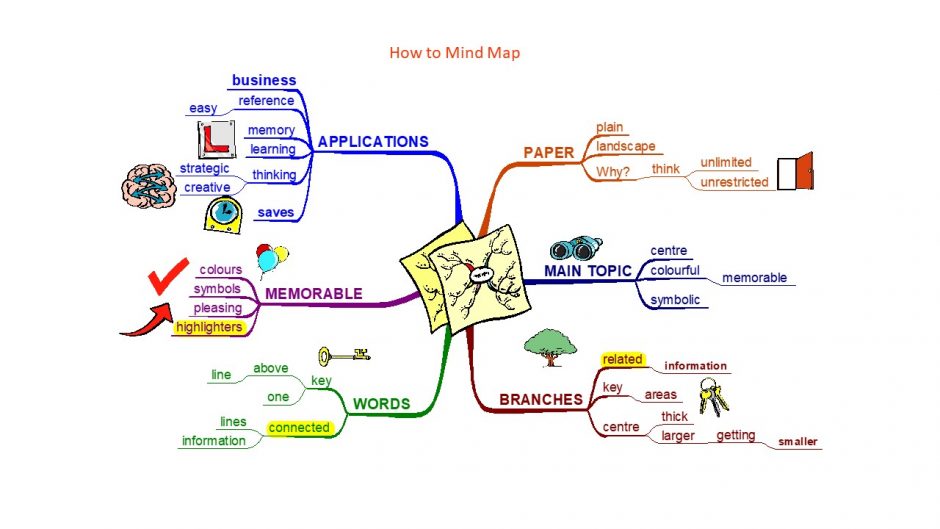

It would be fair to say that Mind Mapping (a technique to capture thoughts, ideas and facts into key words on one page) changed my life. It gave me a method that helped me to remember information, develop ideas, and record presentations. It boosted my confidence in my brain – reminding me, aged 42, that I had a brain that could work well when given the right tools! It also gave me a training programme to offer to schools and organisations when I set up my business, Positiveworks.

The person responsible for developing the skills I learnt and shared with others was Tony Buzan, author of Use Your Head and many other books on how to use your brain to best effect. He died suddenly and too young on 19 April this year, aged 76, after a fall. He believed 100% in the skills he taught and travelled the world in his effort to enable others to build what he termed ‘mental literacy’. He was an impressive individual, not always an easy man, perhaps a little over-blown, but he changed my perception of my abilities and did the same for many thousands of others.

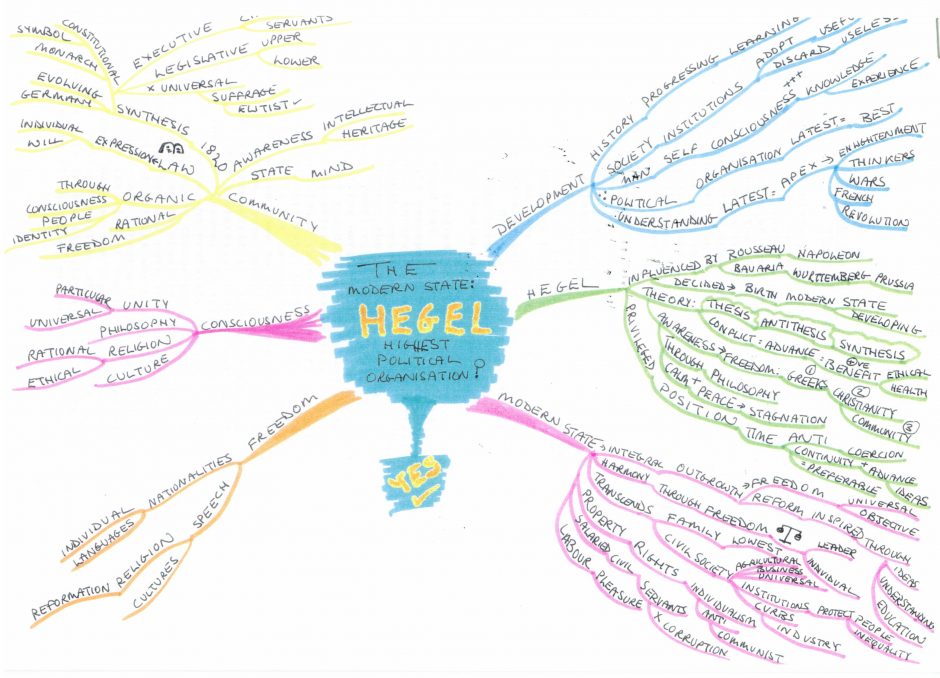

I first came across Mind Maps when I was studying for a History degree at King’s College London, as a mature student. I was thoroughly daunted by all the facts I had to learn and hadn’t written an essay since A levels, twenty years earlier. Then one of my younger student friends, Christian Rogers, suggested I try Mind Mapping. He told me how it had helped him catch up with his A level study after a prolonged illness. He was a firm believer in the technique and, indeed, the mapping technique enabled me to condense huge quantities of history notes down to one page, in a visual format that was easier to remember. Basically, Mind Mapping helped me clear my brain and focus down to the key points I wanted to make. Here is my essay plan on Hegel, condensed from some 30 pages of notes.

After my degree I went on to do a Postgraduate course to gain my Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development qualification at Thames Valley University. The tutor teaching us Communication skills was Lex McKee, who happened to be a devotee of Tony Buzan’s work not only in Mind Mapping but in Memory skills too. So this was another step on my ladder towards training with Tony myself, which I eventually did in Bournemouth, where Richard Israel (later my co-author on Your Mind at Work and who sadly died young too) and Vanda North (very much alive and kicking!) were running the Buzan training course.

Few of my friends or family understood why I wanted to spend a considerable amount of money on doing this Buzan course. “What’s it for?” “Where will it lead you?” “How will it make you any money?” But something in my gut drew me towards it and I put their well-intentioned concerns behind me and did the training. It turned my life around and brought in a good income for the twenty five years of running Positiveworks, as I travelled the world teaching others the way to read more effectively, mind map and memorise information, among other things.

I shall never forget the moment Tony Buzan persuaded me to go in for the World Memory Championship, only a month or two after my one week’s training with him. When he first suggested it, I refused, saying “The people who go in for this have practised for years. I have only done one week!”. “But you’re one of my trainers now” he retorted stubbornly “You should give it a go.” And so I did.

Going in for the Memory competition was such a huge lesson in the benefit of feeling the fear and doing it anyway because I actually won the Names and Faces competition (to remember as many as possible from 100 in 15 minutes) and also another competition to remember which images had been shown from a set of slides. This boosted my confidence enormously and convinced me that the techniques worked. It motivated me to share these systems with as many other people as I could in order that they could benefit from understanding how to make the most of their minds.

And so all this moved me towards setting up Positiveworks, with the strap line Positive People=Positive Results, determined to enable others to adopt new ways of thinking and learning that would release them from the clutter of thoughts and facts that could get in the way of good analysis. My additional training in cognitive-behavioural coaching and NLP supported this aim, integrating theories that enabled people to think effectively and helpfully about life and/or the subjects they needed to consider.

Aged 15 my son Rupert created this rather good image for my business!

Years later he used Mind Maps for his Chartered Financial Analysis qualification and his 8 year old daughter Emmeline, my granddaughter, uses Mind Maps to help her remember and recite poetry for school.

So I shall always be grateful to Tony Buzan and to all those who happened to be there to guide me towards that path. Again, when I think of those people, I am driven to reflect on whether there was some kind of destiny involved. Looking back on it now it does almost feel as if there were hands drawing me along from one step to the next. I wonder if any of you have had similar experiences in your own lives?