Home

Nov 30

2016

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I don’t know about you but I found the interaction between boys and girls pretty confusing when I was growing up. At my kindergarten the boys would chase me with stinging nettles and spiders and yet I was the one who got into trouble when I screamed. The teachers didn’t reprimand the boys for scaring me. This seemed thoroughly unfair and left me with a sense that they were more powerful than I was. I was relieved when I moved on to an all girls’ school. But did this then cocoon me in an unnatural world where I wasn’t learning how to manage the opposite sex? Or sex? I do remember being rather horrified when boys tried to touch me up at teenage parties and finding it tricky to balance being polite and considerate with being firm enough to say “no”.

In a week where we have learnt of the sexual abuse of boys by football coach Barry Bennell, it becomes clear that young children find it difficult to assert their rights, even when they know that what is being suggested is wrong. Yesterday morning on the Today programme Maria Miller, Chair of the Women and Equalities Select Committee, recounted that 2/3 of girls in school report being harassed sexually by their male peer groups, being called names such as slut or whore, being touched inappropriately and being rated for sex appeal. I feel lucky that didn’t happen at my school.

Ranulph Fiennes recently spoke very movingly about his own experience of being sexually harassed at school, which he writes about in his book Fear: Our Ultimate Challenge (Hodder & Stoughton). We need to help girls and boys find the language and behavioural skills to manage these bullying situations as today’s young people can suffer not only in the playground but also through social media, sexting, and at home. Mental illness among the young is increasing and incidents of bullying and harassment can lead to conditions such as depression, anxiety, self-harm and anorexia, so the more skills we give children to counteract these experiences the better for them, their families and also for the hard-pressed NHS.

It may seem strange but I didn’t realize until mid-life that I had as much right to my opinion and needs as the next person. I, like many girls, was brought up, both at home and in school, to be helpful, polite, accommodating. I am not alone. In my experience many people only learn about assertiveness skills and managing conflict when they are in their 30s or 40s and are sent on a training course at their place of work. But we need to be taught these behaviours earlier in life. Saying no is difficult in many different situations. I know many people who find it tricky to say no to a boss’s demands on a project at work. I knew girls who had sex with boys because they felt it too impolite to say no. They didn’t necessarily want to make love but felt that a rejection might be rude, uncool, or hurtful to the boy. Looking at the research on today’s teenagers it would appear that this still happens.

We are basically talking about power and how to enable children to feel powerful in themselves but not have to wield that power over others. It isn’t always easy to speak up for yourself, especially when the other person is older than you or in a position of authority. But it has to start with the self – with each individual working out for themselves what their personal boundaries are, what they are or are not willing to go along with, whether in relationships or in other areas of life such as drugs or crime. If we don’t have this clear within us then we can’t express it to others and there is no reason why they should be expected to know it intuitively.

The need to know what one stands for and where one is going was brought home to me when I did a leadership day with horses, which I may have mentioned before as a life-changing moment. I was put in a ring with a horse with no bridle and I had to somehow persuade him to follow me. It was only once I became absolutely clear where I wanted him to go and had embodied that sense of direction in my body language that he deigned to follow me. I had to make my intention clear to myself first and not give fuzzy or ambiguous messages. When others know what you stand for they often – though not always – respond with respect. We can help young people to be prepared for either.

Growing up is complicated. Well let’s face it, life and other people can be complicated! We have to learn to develop the confidence to express our needs and opinions. Schools can provide a safe environment in which children can begin to think about the social areas of life. They can introduce topics such as values and principles and, through questions, help the child to identify their own set of values and boundaries. My colleague Diane Carrington and I wrote a book on this subject called Future Directions: Practical Ways to Develop Emotional Intelligence and Confidence in Young People (Network Continuum). In my own life I have found role play to be invaluable in integrating new behaviours as one literally has to learn new words, voice tone and body language in order to convey firmly enough what one is requesting or rejecting. One has to practice and rehearse the words sufficient times so that one’s response becomes built into muscle memory. This develops a sense of self and one’s rights that are firmly centred within.

They always say that you end up teaching what you need to learn and I did, indeed, find myself teaching assertiveness classes when I first set up my business, Positiveworks. I taught others and therefore learnt for myself that to be assertive means:

- Respecting yourself and giving respect to others. Recognising that you have as equal a right to your opinion as others do. You may have different opinions but can still honour one another.

- Taking responsibility for yourself, including the recognition that you have a responsibility towards others in how you communicate and act.

- Knowing what you want, feel or need and asking clearly for it by expressing your needs and feelings honestly but without punishing people or violating their rights.

- Being able to say no, or that you don’t understand.

- Being clear about what you want to accomplish, and then being prepared to negotiate on an equal basis of power rather than trying to win.

- Allowing yourself to make mistakes, to enjoy and talk about successes, to change your mind or to take time over a decision.

I was obviously a late starter but I came to see that each person has a right to their own opinion but not a right to force that opinion or need on others. And that you can say no to another person just because it doesn’t feel right to you but you don’t have to be unpleasant. You learn the language that helps you feel strong enough in yourself not to give your power away to another person or compromise your values. Useful phrases can include “No thanks, that doesn’t work for me.” “I can see what you’re saying but I don’t agree”. “I’d like to think about it.” “ I’ll decide when I am ready.” It’s the tone of your voice that will tell the other person whether you are choosing to be rude or whether you are understanding their position but holding your own position. It helps to keep your inner thoughts supportive too – such as “Just because the other person wants me to do something doesn’t mean I have to do it. I am the director of my own life, I can say no if I want to.” In this you have to become willing to be unpopular or be subjected to put-downs, called a spoilsport or worse, because ultimately you know that it is better to stand up for yourself than it is to be popular with others on their terms.

This is particularly difficult in teenage years, of course. Parents and teachers can support young people in these situations but only if they open their eyes to the kinds of challenges their children are experiencing and are willing to talk about them. Sex education is still often taught on a biological level. The assertive behaviours required in multiple situations in life and work often don’t get taught at all.

One doesn’t want to frighten a child but bringing these issues out into the open can help them be prepared and plan their response in advance. Teachers can be role models of assertive behaviour in how they discuss and deal with both boys and girls equally – unlike the teachers at my kindergarten. They can show zero tolerance of disrespectful behaviour on any level. Learning to manage conflict or demands are essential social skills that can be readily shared with children at school and at home. The earlier they are taught the better. They are life-skills.

Links: Future Directions by Helen Whitten and Diane Carrington https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Future_Directions.html?id=FY2tAwAAQBAJ&source=kp_cover&redir_esc=y .

NHS advice: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Sexandyoungpeople/Pages/Itsoktosayno.aspx

Nov 24

2016

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I woke this morning realizing that I am one of the luckiest women in the whole of the history of the world. Born in 1950 I missed the impact of war, though its aftermath shaped my childhood and made me value the peace we experienced in England. Yes, girls were still regarded as less important or intelligent than boys and we were told to become secretaries, teachers and nurses rather than managing directors, pilots or doctors but the social and political changes of the 1960s overturned much of those attitudes and we did, indeed, become more than had been anticipated for us. With the pill, for the first time in history, we gained control over our lives with an ease that no previous generation of women had experienced. We could plan the number of children we felt we could manage financially, enabling us to work alongside motherhood and to become economically independent. Research overturned the concept that women were not as intelligent as men and we achieved excellent results at school and university, providing career opportunities we hadn’t thought possible.

I want my granddaughters to be as free and empowered as we have been. But I have fears that there are forces potentially trying to turn back the clock to a time when women had less power and influence. Trump’s anti-abortion and misogynistic rhetoric puts such attitudes centre stage. In addition, lad culture, internet porn, those who resent and berate feminism such as Milo Yiannopoulos, Erdogan’s reforms, plus integration with radical fundamentalist cultures who believe women to be inferior to men, could reverse the changes I have enjoyed. We have witnessed leaders introducing repressive regimes in Iran, Afghanistan and in countries across the globe. Let’s be watchful that we don’t sleepwalk back in time on these issues…

Throughout many parts of the world today women still do not have the same legal or voting rights as men. Women the world over, eg half the human population, throughout history have been treated as inferior mentally and emotionally. Social behaviours and laws have been developed to control them and, until the 1960s we could not easily limit the number of children we had so women frequently experienced multiple pregnancies and births. Death in childbirth was common and the effort of carrying and raising that number of children was gruelling. This remains the situation today for women in many other parts of the world.

Life changed for those of us born after the Second World War. We began to see that we were just as bright and capable as men and men started to adjust to treat us as such. Our relationships became generally less subservient and in the western world men have taken an almost-equal role in raising the family, cooking and sharing the responsibilities of home life. As a single woman I was able to take a mortgage – a simple right that was denied previous generations unless a man signed the deed for you. I set up a business, borrowed money to invest in that business, travelled the world on my own without hassle.

In my youth it was edgy for a woman to go into a pub or cinema on her own. Today we can go where we choose. Whether single or in a relationship the opportunities to participate in culture, travel, clubs and social life has been easy for me. Now, as an older woman, the opportunities are amazing in comparison with those of previous generations.

Equal pay and equal rights aren’t working perfectly but I think young women can’t imagine how different it was for their mothers and grandmothers, some of whom had worked in the war but then were hurried back to the kitchen. I and my peers have benefited from the NHS and medical advances that would have amazed and potentially saved the lives of our grandmothers and their children. It’s easy to forget how dangerous and damaging back-street abortions were too. Girls put their lives and health at risk and seldom took the decision lightly. Those who carried their babies to full-term were ostracised and had to have them adopted, at great personal cost. Don’t let’s go back there.

We have had a tendency in this country to accept behaviours that are unacceptable, including forced marriage, FGM, bigamy, domestic violence, honour killings and women losing their children post-divorce. We have fought hard to change the lot of women in the UK within a very short time. What the suffragettes started was carried on but it isn’t so long ago that the generation of women born before the Second World War were frequently subjected to the kind of behaviours we see in Mad Men, where men felt entitled both to touch and undermine them. Those men would have found it hard to conceive that their secretaries might one day become their bosses. We can’t tolerate a return to that sense of entitlement that existed then but internet porn and lad culture do indeed threaten to turn back the clock and encourage men to abuse girls, as the research in Peggy Orenstein’s book Girls and Sex demonstrates [Harper Collins].

It’s too easy to lose what one doesn’t appreciate. Think about your daughters, granddaughters, nieces and the future generation of women wherever they may be. We need to protect their dignity and their freedom to contribute to business, the arts, science, politics and more, with their minds and creativity. Our sons and grandsons benefit too where there is a balance of equal respect. The world needs the voices of women in senior positions to counteract Trump-style chauvinist behaviours that could otherwise overwhelm us. Those countries where women work and are in positions of influence do better economically and are civilised places to live. We all need to be alert to any chipping away of women’s position or respect. It’s not a joke. Generations of women and girls have suffered and still do across the globe.

Speak out, write about it and complain should these rights and freedoms be put in jeopardy. Not just for your own family and friends but for the whole of civilisation. 50% of the human population has just as much right and just as much to offer as the other 50%. It may be different but it is every bit as valuable a contribution to humanity. Let’s work together to ensure that male and female voices have equal status in taking the world forward in 2017 and beyond.

Nov 08

2016

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I have had an uplifting couple of days visiting Salisbury, an old haunt where I was confirmed and where my sons were at school, and then driving down to Devon through the most beautiful landscapes of autumn. What a stunning country we live in. I do enjoy the changes of the seasons, the sweeps of fields, hills and golden woods. I enjoyed noticing the horses, cows and sheep grazing on the green grass and my journey was an enriching experience. I felt fortunate to inhabit such beauty.

And I have been questioning how it is that I know those things that uplift me but don’t always make sufficient time for them. It’s so easy to get buried in emails and lost surfing the internet. All very interesting but this seldom raises my spirits in the way that, say, standing under a night sky does. When I had a flat in Nice I would sit on my balcony almost every night looking up at the stars but now I live in the countryside, where the sky is clearer and less light-polluted, I hardly ever remember to get my fix of wonder by going out into the garden and looking up. More fool me.

So I have been thinking about what it is that makes one person experience a sense of awe from being in a sunset or a sacred place and another from being in a science lab. Where do you gain your sense of wonder?

For me it’s cathedrals. Put me in a cathedral with a choir singing and I am transported to another realm. I can’t help but experience a sense of wonder. I don’t have to think about it. It just happens. I look at the beauty of the stained glass, carved wood, towering arches and something happens inside me, unbidden. Awe.

I was visiting Salisbury in the hope of finding the gravestone of an ancestor, Thomas Bucknall. He is recorded on our family tree as having been buried in St Edmund’s Church Salisbury in 1783. And so I spent Sunday afternoon wandering around damp graveyards only to discover that St Edmunds is now deconsecrated and has become an Arts Centre. No-one I spoke to seemed to be clear about what had happened to the graves.

And so I moved on to the church of St Thomas, in the centre of Salisbury, to see if anyone there knew where I might find information, as the parishes were amalgamated in 1973 becoming St Thomas and St Edmund’s. What a delight that was – a chapel with medieval wall paintings and, above the Chancel in the main church, a Doom Painting, depicting a Bishop being dragged to hell. But the concept of doom brought my mind back to the US election, to Syria, Brexit, Mosul and the hope that doom would not be coming our way soon.

I have always been drawn to sacred spaces and sacred music. I don’t really know why as my parents weren’t particularly religious. I think it may have been due to my prep school headmaster, John Booker, or Mr B as we called him, at Knighton House in Dorset. The Bookers had created a simple white chapel in the basement of the school and Mr B took our services. I still remember him often, as a warm, wise and spiritual man. His wife, Peggy, led the choir and carol services in the local church in Durweston. For me it was a special time and I continued to enjoy going to church even though my next school, Cranborne Chase, did not push religion down our throats and many of my friends weren’t interested. But we were encouraged to think about what it meant and to me it resonated and has been a part of my life ever since.

David and I are lucky to have Winchester, Chichester and Salisbury cathedrals all within a short distance and can go to services or listen to sacred music. On our travels in Russia and Eastern Europe we visited Orthodox churches with exquisite wall paintings and were given concerts by black-robed Orthodox priests with their sonorous bass voices. Fabulous.

And so on Sunday night, to shelter from the cold and from the potential doom of the US election, I took myself to evensong in Salisbury Cathedral. As I walked down the nave that familiar sense of wonder took me over. I looked up to the ancient stones and thought of the history of the kings and bishops who had walked the flagstones over the centuries. And felt angry again that the government are potentially dropping History of Art from the school curriculum. Whether or not you believe in Christianity these churches and cathedrals and the art within them hold our history. I remember my mother being horrified by a young woman next to her in a jewellery shop who looked at a gold crucifix on a chain and asked, “who’s that little man?” Will generations to come know anything about the stories and beliefs that have shaped our past?

I have noticed that a building takes on the energy of what happens within it. For me a cathedral presents an energy of wisdom, as if the centuries of worship and song have seeped into the stones, encouraging us to be still, to reflect and question what we can learn so as to access the better part of ourselves as we go back out into the world.

The bishop spoke of truth and wisdom in a thinly-veiled attack on the “post-truth” politics of Trump and Clinton. He reminded us of the Magna Carta housed in Salisbury Cathedral, implying that we should take the judiciary seriously. And the choir sang the Nunc Dimitis and Magnificat, their pure young voices echoing around the aisles. Truth, wisdom, forgiveness and love, yes, good values to hold within us whether we believe in Jesus Christ or not.

I left feeling uplifted, reminding myself that it is up to me to seek out these moments. They exist if we look for them – in the night sky, in music, a painting, a sunrise, in the innocence of a child, a cathedral. In this uncertain world we can still find wonder. Each of us will see awe in different places. It’s up to us to make it happen.

Nov 04

2016

1 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

How accurate is your memory of the past? Of your family? Of past events? Do you find that siblings, partners or colleagues have contrasting views of an experience you shared? People tend to notice and remember different aspects of a situation or project.

David and I have just been travelling the Danube from Budapest to Bucharest. It was a tour organised by The Daily Telegraph and Emerald Waterways (www.emeraldwaterways.com). The theme was war. We were treated to lectures from BBC foreign correspondents Nick Thorpe, talking about Budapest and the Danube, John Simpson covering the fall of Ceausescu in Romania, and Martin Bell who travelled with us and enlightened us with his experiences of the Croatian Wars. It was a fascinating trip on a luxurious and expertly-run boat and in the company of some delightful, educated and interesting fellow travellers.

I came away with many impressions of post-Communist Eastern Europe and two particular questions kept coming into my mind as we tried to piece together the various narratives we heard from our local guides, the journalists’ lectures and the people we met on the street. First, how do people find the stoicism to survive the terrible personal suffering of war? Something I suspect one can only know by experiencing it and I hope I shall never do so. Second, how do we find the heart of the matter when so many perspectives and personal experiences differ, when memories are often clouded by emotion and filtered by belief? What and where is the truth within these complex events: what is history?

We visited towns and villages in Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania. In each place we had an individual tour guide and each guide offered a different perspective. This was particularly true in Croatia where the responses to the question of how Croats and Serbs now live together were markedly contradictory. We all had hosted lunches with different families. In our family there were two daughters, their parents and two children. Their experience of the war had been that their house had been 70% ruined by mortar shells and they had escaped to Austria while a Serb family lived in their home for five years. The Serb family had been in touch with them throughout this period and handed them back the key at the end of the war. Now, they told us, Croats and Serbs live happily side by side and go to school together.

Our fellow travellers received strikingly different narratives from the hosts with whom they lunched. They were informed that Croat and Serb children may go to the same school but at different times of the day, so that they don’t mix. Martin Bell confirmed this and reported that even before the war people lived alongside each other because the police made sure there wasn’t trouble. We heard other sad stories of the after-effects of the war where a husband had been killed by chemical gas, young men maimed physically or left with PTSD, some never able to work again. The fact that the family David and I visited seemed to be of an optimistic nature and united as a unit may have made their perspectives of history different from that of others. Each individual we spoke to had experienced distinct events and had inevitably met those events with their own beliefs and points of view.

I was left with a general impression of the miserable legacy of Communism – the hypocrisy of leaders presenting themselves for equality of all people and yet building themselves palaces and pocketing money. The monotonous and grim concrete blocks built in all the five countries we visited that are now crumbling and decrepit. Our guides told us, as we were told in Russia earlier this year, that their parents sometimes harked back to the certainty of those times, even though they were on starvation rations. There had been more-or-less 100% employment and people had the ability to live, albeit at a meagre level. Today nothing is certain and people are frequently living on as little as 400 Euros per month, with rents taking more than half of that income.

Everywhere we went we heard of high unemployment, low wages, derisory pensions, of corruption in high places, of those who were in Communist regimes remaining in some administrative and political roles. And of how the young are moving away to Germany, the US, Ireland, UK because they see no prospect of work in their own countries, depriving those countries of their brightest doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs who could potentially help rebuild these countries economically.

But I question whether the people who have been privy to occupations or dictatorships find it easy to be entrepreneurial? Communism has treated them as automatons, as groups of people and not as individuals. I wondered, from a neuroscience perspective, whether finding the neurons in the brain to identify innovative opportunities may well not come easily to such people with these histories. After all, their parents lived under Communism and their grandparents often under an authoritarian monarchy, neither of which encourage creative individualism. I don’t believe we can make people think in new ways overnight, any more than we can expect people to embrace democracy overnight when they have not had it for centuries, if ever.

Once again I was struck by how different the history of the UK has been to that of mainland Europe, where they have had centuries of invasions, occupations, dictatorships. We were told that when living under an authoritarian regime people find ways to get around the rules – the black market, whispered deals in corridors to avoid tax, make things happen, or find goods that people want. They call it ‘the loop’. We have not been occupied and have had centuries where our institutions have developed in such a way that most of us abide by what we recognise to be adequately fair rules. Having visited East Europe, Russia and South America over the last couple of years, I am left with a sense that we just don’t know how lucky we are in the UK, that our poverty bears little relation to the kinds of hardship people in these countries are experiencing.

I am no expert and don’t pretend to understand the histories of the countries we visited. But I do think we need to be careful when we are constructing a historical narrative, whether it is about a war, a country, a family or an organisation. Martin Bell was a very enjoyable and insightful companion to have on board the ship with us and brought events alive with his direct experiences of war. And yet explained to us that inevitably if, as a journalist, you are embedded with one group or army unit you gain depth of understanding of their situation at the expense of understanding their enemy, or maintaining a sense of the overall strategy or direction of the war in general.

In his preface to his classic book on the Algerian War, A Savage War of Peace, the historian Alistair Horne writes of how complicated it is to reach any objective truth in a complex and long war, with multiple levels of action and no obvious single focus. A French premier had commented that “only an Englishman” could be adequately objective to see beyond personal perspectives of the Algerian War. In 1580 the French philosopher, Michel de Montaigne wrote that if humans so frequently lack self-knowledge, why should people consider our “facts” about the universe to be reliable?

Post-Communist Eastern Europe consists of many countries who experienced multiple events. Within those events are individual stories, emotions and beliefs about what happened. All perspectives add to the story and have a truth but as these perspectives can be contradictory the real truth of history can be illusory. Montaigne might argue that some humility about our ability to see and remember things clearly is a more realistic description of the fallible human mind. Can we personally be so sure that our own memories of a situation are totally accurate, I wonder?

And a poem inspired by our visit to Vukovar and Martin Bell’s lecture and video clips:

“All Wars are the Worst War” (Sergeant Andy Mason of the Desert Rats)*

The sniper dives behind a shattered door frame,

disappearing into long shadows of waiting.

Time travels both fast and slow

within the confines of his battle.

The windows of the nearby Hotel Dunav are being shot

window by window, floor by floor,

in the concrete Communist block skyscraper

towering over Vukovar’s harbour.

Houses stand bombed and broken.

A neighbourhood street where mothers had cooked,

children had played, grandparents visited,

now unrecognisable. A tumble of jagged bricks and breezeblock.

There’s nowhere to run. Every corner covered,

the wide wild fields of wheat booby-trapped with landmines.

He thinks he is fighting for justice, territory, belief.

He has not lived sufficient years to realize he’s a political pawn.

A mortar blasts and rocks his cover.

He ducks into darkness in the shelled ruin of a shop,

aims his gun into the gloom to discover a fighter

sheltering under the counter, teeth chattering, stupefied in terror.

Snipers firing, snipers being slaughtered, so many being maimed.

No orders reach them. Fear takes over.

Their young-man bravado seeps into the blackness of their hearts,

the futility of war murdering them both in its own way.

*From In Harm’s Way: Bosnia: A War Reporter’s Story by Martin Bell. See this and other poems on this link:

Oct 20

2016

2 Responses

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I have been wondering what exactly people mean when they use the term “foreigners” these days. In my dictionary it is listed as

1.a person not native to or naturalized in the country or jurisdiction under consideration; alien.

2.a person from outside one’s community.

3.a thing produced in or brought from a foreign country.

I am not sure how the Government is currently defining “foreigners” when they talk about them. I think Amber Rudd has a duty to be very specific in her terminology. As someone who is British but was born outside the UK – in Portugal – does she mean that I might be defined as a foreigner? The recent DNA test I had showed not only Anglo Saxon and Irish blood but also some percentage of North African, Middle Eastern, European Jewish, Italian and Greek. What does that make me?

A recent survey carried out by Ancestry.com revealed that the average UK resident is 36.94 per cent Anglo-Saxon, 21.59 per cent Celtic and 19.91 per cent Western European, from regions in France and Germany. Our ancestors surely travelled – for war, territory, love and religion so the concept of nationality is more complex than we might imagine. But I think that what people perhaps mean when they talk of foreigners is people whose customs are different to our own.

The brain is programmed to identify a threat. Way back when, our caveman ancestors would have sought to defend his tribe from any stranger that might have eyes on either his wife or his territory, or both. I think it helps to understand that this is a basic human survival mechanism. It would happen to any human being anywhere in the world when they perceive someone whom they perceive as a threat. We don’t have to beat ourselves up about it but we do need to understand that as citizens of the 21st century we have choices as to how we manage and respond to these primitive survival mechanisms.

We recently went to the Revolution exhibition at the V&A which covers the demonstrations that were taking place in the 1960s supporting peace and equality, gay, women’s and black rights. We may not think we have come a long way but believe me it is certainly better than it was then. It may not be perfect but we do have legislation that attempts to protect these rights now and we have sought peace even if we haven’t been able to protect the world from dictators.

But my point in this article is that we can choose to see beneath the skin to our shared human condition. As a coach I have had the privilege of having intimate conversations with people from all walks of life in many different parts of the world. In these moments I have been struck again and again by how similar are the concerns of human beings. People grieve at the death of a loved one, celebrate the birth of a healthy baby, worry about their bodies, their weight, their love life, their finance or careers. People are challenged by technological change and by work-life balance. Stress has become a more prominent feature of consciousness everywhere I have travelled.

Our bodies and emotions are part of our shared humanity. It is our minds that can divide us. We have developed the habit of categorizing everything – animal, vegetable, mineral, gay, black, white, Muslim, Christian, Hindu. This can be helpful but is often too binary. Someone may have come from another country or religion and yet have very similar values and attitudes to us. Another may not but they may both be placed in the same categorization pot by a newspaper, government or stereotype. A train that is over-crowded does not categorize its passengers. Whether they are striped or polka-dotted, the train is still either full or empty. It is the human mind that judges and categorizes.

Within our shared humanity is the ability to analyse and choose our response. The environment in which we live is continually changing. We continually change within it. Therefore some of the beliefs, expectations and thoughts that we have about who is like us and who isn’t may well be out-dated. The model below is one I developed early in my coaching career to help people recognise that at any stage of life we can reflect on and change our conditioned and habitual responses:

positiveworks-5-step-thinking-system

As a grandmother I hear my grandchildren talk about things in the same terms as their parents – whether this is about religion, literature, TV programmes or politics. As young children they are inevitably dependent on their parents for survival and it is natural for them to do this. As they become teenage no doubt this will change and they will rebel! And yet you often find that people do maintain the same political and religious inclinations as their parents throughout their lives. If the Dad is an Arsenal supporter then the sons are likely to be too – and will define themselves separately from a schoolfriend who supports Chelsea. It is just as tribal as our cavemen ancestors.

We are facing a challenging time ahead on several fronts with Brexit, the possibility of Trump in the White House and with the upheaval in the Middle East. This is surely a time when we need to be careful of our language when we discuss these problems and negotiate our relationship with the rest of the world. People may not be keen on EU bureaucrats but that doesn’t mean to say that they don’t like Europe and the Europeans. We may need to be wary of those who are out to do us harm but this does not mean that we have to be wary of all foreigners. It is time for Governments, media and individuals to use words precisely.

For beneath the skin, whatever our colour and provenance, our hearts beat, our digestive system processes food and our lungs breathe. We all suffer when we lose a loved one, laugh, dance, make love, worry about our children, wonder at the beauty of a sunset. As we go forward perhaps we need to be more aware of how our minds have the potential to separate us while our shared humanity has the potential to draw us together to solve the world’s problems. Or am I just being a 1960s Baby Boomer utopian!?

Oct 06

2016

0

Comments

Helen Whitten

Posted In

Tags

I am re-reading Emma Sky’s excellent book The Unravelling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq, in which she describes her experiences as an advisor to the US army during the rebuilding of Iraq post 2003. It has brought home to me once more how important it is for leaders to take psychological and emotional responses seriously. Again and again she makes it clear that the Coalition were not thinking rigorously enough about the psychology of those with whom they needed to interact. They were missing out the human factor of emotion, family groupings, tribes, religious sects and communities. They didn’t appear to be taking into account that how people feel emotionally about events will shape their individual and group behaviours and responses.

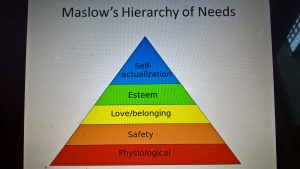

It hadn’t seemed to occur to those leading the bombardment to think ahead to how it might feel for Iraqis to have America bomb Saddam and his troops. Yes, people may well wish to be rid of a dictator, be they Saddam Hussein, Gaddafi or Assad, but it is a different matter to have a foreign force invade and then occupy their country – particularly if that occupying force have not considered safety and comfort after the event. The Coalition quickly lost the goodwill of the Iraqi people by not having had a vision of success that included stable government nor providing the people with water, electricity and supplies. It might have benefited the Coalition leaders to remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs where he argued that if the basic physiological needs of food, water, sanitation and safety are not put in place people cannot rise up to levels of healthy communication:

Little was learnt after Iraq in the toppling of Gaddafi in Libya where the country was once again left in a state of disintegration, allowing it to become a breeding ground for the so-called Islamic State in the chaotic aftermath of that debacle. Once again in Syria one sees little evidence that the Coalition forces have stopped to consider who they are dealing with on a personality level and how best to communicate with them in the government, the Syrian people – or Putin.

Over many years working in the business world I have experienced a disparaging attitude to psychology, which they often dismiss as “psycho-babble”. I found leaders paid scant attention to the practical theories that psychology books can provide. Often the focus on people-matters is still regarded as a soft and woolly area rather than the serious ingredients of what can help leaders motivate and incentivise their staff to action.

When David and I attended a lecture last year describing a research project at Cambridge University on the subject of conspiracy theories we were shocked to hear that there was no psychologist in the team. The talk included discussion of the MMR vaccine, the supposed assassination of Princess Diana, and the idea that the US plotted 9/11. The examples contained many elements that related to the behaviours and psychology of those involved in conspiracy theories: those who instigate them, those who believe in them and those who don’t. Surely it is obvious that the belief systems of anyone involved in conspiracies would be shaping their susceptibility to either develop the conspiracy or to believe in it.

Do senior political figures read books on psychology, I ask myself? If they did I would be surprised if they would talk about others in the negative terms they often use. The egos of those in power are frequently far more sensitive than they might appear and it does make sense to stop and consider how Assad, Putin or Juncker might feel if they are referred to in a pejorative way. Talking down to this type of person might simply lead them to retaliate. The appalling rudeness that Farage, Boris Johnson and the Leave campaigners used during the Brexit campaign demonstrated all too clearly that they had not given a thought to the fact that they would inevitably need to continue to work with the members of the EU about whom they were being so derogatory. Jeremy Hunt could also learn much about how to present a case in a way that might stimulate cooperation, could he not? And how about the talented and motivated individuals who are contributing great value to our country – how might they feel when described as “foreigners”? Perhaps a read of books such as Games People Play , Where Egos Dare or Difficult Conversations might have given them some insight as to how to smooth the waters of negotiation?

Might the Coalition in Iraq have transacted differently with Maliki if they had better understood his tendencies to authoritarianism and that you can’t change people’s behaviours overnight? As it was, both General Odierno and Petraeus were wise enough to recognise that Emma Sky provided them with insights into building relationships in Iraq that they personally did not have the gifts to discover themselves.

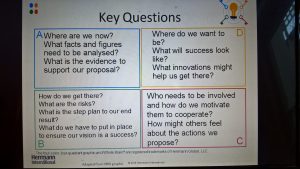

Much respect is given to the efficacy of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and yet those who govern us do not appear to have understanding of how they might themselves apply it to their leadership. If the premise of CBT is that thoughts, beliefs or expectations shape feelings and that feelings shape behaviours then the simple set of questions for an government to ask might be:

- What are we trying to achieve here?

- What does success look like?

- If this works how might those involved feel?

- If they feel like that then how might they behave?

- In taking this into account what are the risks and what is the best way to act or communicate?

- What are our priorities and what do we need to do first?

This process helps leaders include the element of emotional intelligence that seems to be missing from so much of the leadership we experience in government, business and the military. A country is made up of individuals who think and feel. The EU may seem a large bureaucracy but it is composed of individuals who have a sense of their own status and dignity. If people insult them that will have negative consequences. It seems obvious but I have witnessed many initiatives where no one is totally clear about what they are actually trying to achieve, nor how people might feel emotionally if they were to achieve it. In Iraq this seems to have been as true about the Iraqi factions as it was about the Americans. I wonder now whether the Coalition forces or the Syrian rebels have a clear vision of success for Syria? People shoot themselves in the foot by not shaping the positive outcome nor taking the emotional factor into account. Where people feel respected and included they are more likely to work collaboratively towards intended goals.

The trouble, as I see it, is that whether it is Iraq, Libya, Syria, Brexit or the NHS, no-one really seems to have worked out a clear joint vision of success or if they have it is opaque. Without this it is impossible to develop a plan. “Begin with the end in mind” is the advice in Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, followed by “seek first to understand and then to be understood”. Both these statements relate to the right quadrants of the HBDI model below – the yellow quadrant of positive outcomes and the red quadrant of people, emotions and behaviours. Both these quadrants are, in my view, the most neglected areas of attention of leaders worldwide. As Emma Sky was aware, the world revolves on building relationships of trust and none of us can afford to forget this.

Whether it is a military operation in Iraq, the harbouring of a conspiracy theory or running an organisation, the perceptions, beliefs and emotional responses of those involved either perpetuate a problem or help solve it. Common sense, you may well say, but how often do we hear this complex but essential human factor specifically discussed in board rooms or parliament? And whilst leaders continue to discount psychology and its impact on the behaviour of those they work with, we shall surely continue to see failures of initiatives when those in charge blithely ignore how their actions might make people feel emotionally.

Some further reading suggestions:

Where Egos Dare: The Untold Truth about Narcissistic Leaders and How to Survive them by Dean McFarlin and Paul Sweeney

Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss what Matters by Bruce Patton, Douglas Stone, Sheila Heen

Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships by Eric Berne

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

Cognitive-Behavioural Coaching Techniques for Dummies by Helen Whitten

Emotional Healing for Dummies by Dr David Beales and Helen Whitten

Saneworks by Chris Welford and Jackie Sykes