I’ve known some. For my infant son, my parents, sister, grandmother, aunts, cousins, friends, marriage, relationships, pets and most recently my cat, Chico. There was a poignant discussion on Woman’s Hour recently about the depth of grief one feels for a pet and the complex emotions that go with this. After all, it’s only a cat, right? And yet a pet shares one’s daily life, moods, routines and rituals in a way that close friends don’t. Even in a marriage or relationship each one of you relates to that pet in different ways. And when you live alone the intensity of that relationship with your pet is inevitably ramped up.

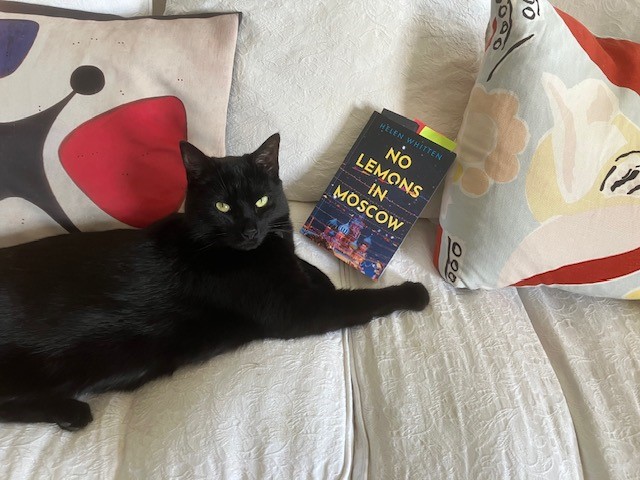

And so if I have been rather quiet on the blog front it is because my cat Chico had to be put to sleep recently and I have been knocked for six by this. He was the second cat I have held in my arms while he went peacefully to sleep and each time I hoped that the Assisted Dying Bill would be passed for we humans, who may be put through far worse traumas than an animal at our death. I’m not optimistic that the Bill will go through.

The distinction with Chico is that he has been a part of my life after retirement. A period when one is less busy, less preoccupied with work or colleagues or family, as one’s family are now happy independent units to themselves – which is what one would wish for them. And so the fact that your cat bothers to greet you at the door when you come in, sits with you as you watch Slow Horses and insists on wrapping itself around you as you try to sleep takes on a greater significance than it would if one was busy with children or work.

A friend commented that she was perplexed when people express surprise at how grief impacts them and yet each loss is so unique that it is inevitable that each grief hits you in an equally unique way. One hasn’t lost a mother before, then a father, or vice versa. Each friend represents a unique relationship that has brought out aspects of oneself one may not have shared with other friends. And at my time of life losing friends happens horribly often.

People imagine that death was more commonplace emotionally in times when half one’s children would have died from illness and yet letters and diaries suggest that each loss was deeply felt. It’s human. Where there was love there will be grief when there is loss. I am aware that I witnessed my mother losing friends in old age and perhaps had a similarly misconceived assumption that it was easier as you got older because it is surely inevitable. But, of course, it isn’t easier. Your friends are immensely important at any stage of life but perhaps particularly as you age, for they know and understand you well and they also understand the challenges of ageing.

Another type of grief is experienced with illness or dementia, where I am witnessing friends losing the person they love – spouses, parents, friends – before they actually die. Stages of grief slipping into daily life as an illness chips away at a loved one.

I’m not sure one ever fully recovers from the death of a child. Nearly fifty years on it is still important to visit my son’s grave and keep the memory of his nine short weeks of life alive for myself and the family. And all those whom one has lost live on inside us. I’m not alone in thinking of my parents, sister and grandmother every day, and of missing the conversations I would have been having with them and with the friends who have died before me.

I was with both my parents, my son, and my sister as they left this life. And my two cats. Each one a precious being in this world, leaving this world. Perhaps I shouldn’t feel so surprised that Chico’s death has hit me this hard. The house feels echoingly empty without him. But this makes me think of other friends who have recently lost partners with whom they have shared the whole of their adult life. How can it possibly be comparable? In most ways it can’t and yet I still remember the day my father returned from the vet having had to put our golden labrador down and seeing him cry for the first time. I was probably around 10. These creatures certainly find their way deep into our hearts.

Although it is sad and uncomfortable, at the same time to grieve is to live, to feel, to appreciate what one has been lucky enough to enjoy and experience as part of one’s life: the love of a parent, sibling, spouse, friend, or pet. As Khalil Gibran wrote “You are weeping for that which has been your delight.” How lucky are we to have experienced that love and delight. To grieve is to be human and to be thankful.

Poems on https://www.babyboomerpoetry.com/poems/goodbye-chico/