It’s 100 hundred years since Sir Frederick Banting and his laboratory team discovered insulin and we began to understand how it interacts in the body. I knew nothing about Diabetes Type 1 until my bright and beautiful granddaughter Emmeline was diagnosed with it aged 8. It came out of the blue and presented a steep learning curve for her, my son and his wife, and for me as a granny.

Emmeline, like many other children living with Type 1, is stoical and determined to live her life in the way her other friends do. Nevertheless, the reality is that her life has been changed by the diagnosis and that she and her parents have to be aware of the level of her blood glucose 24/7. Keeping her, and the other approximately 29,000 children living with Type 1, within normal blood glucose range takes time and attention.

Her childhood cannot be the same as another child’s as she has to weigh and measure everything that she eats, including any sweetened or fizzy drinks, calculate the carbohydrate content, and adjust the measurement of insulin accordingly. When she comes to stay, I have to get with the programme in terms of weighing and measuring and monitoring everything to keep her well. Attention continues into the night, as her levels can raise or dip, and need correction, whatever the hour. She has to carry her emergency bag of glucose and syringe with her at all times in case of hypos.

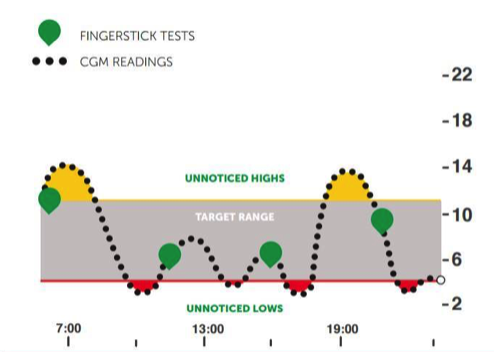

But life for today’s children is vastly improved from the days when a prototype insulin pump was as large as a backpack. Nowadays an insulin pump will fit into a pocket, like a small mobile phone. And continuous monitoring is available through technology that keeps check of levels and sends them to a parent’s smartphone so that the parent can be in a business meeting many miles away but can alert the child and their school that a correction needs to be made, or a glucose pill swallowed, to rebalance the level.

And my granddaughter has received brilliant and world-class support from St Mary’s Paddington and the Hammersmith Hospital and JDRF (Junior Diabetes Research Fund) provide a resource of emotional support and information, as well as being the largest non-profit organisation carrying out research into Type 1, its causes, symptoms and treatments. Their aim is to create a world where Type 1 no longer exists through discovering how to prevent it.

But for now it is not preventable. There are many misunderstandings about diabetes and the key is the difference between Type 1 and Type 2. Type 2 is a lifestyle problem. Type 1 is an auto-immune disease. This means that it is not due to a child eating the wrong thing or living an unhealthy lifestyle. It is due to that child or person’s immune system malfunctioning to attack and destroy the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Insulin is crucial to life and needs to be managed carefully as otherwise it puts pressures on various areas of the body such as the brain, kidneys, eyes and nervous system. The management of insulin levels has vastly improved the risks.

I wish the media would be more careful in their reporting of statistics around diabetes, as they often lump both Types together and do not make the distinction between Type 1 and 2 in their reporting. It is this laziness that perpetuates many of the myths around Type 1 and it’s time they became more knowledgeable about the difference.

The symptoms are significant thirst, needing to go to the loo often, and fatigue. It takes a parent being on top of this to notice, google and take the child to the doctor. They often require hospital treatment to rebalance and start the process of finger-pricking, injections and monitoring to achieve normal range levels.

Although today’s technology means that a child’s life is less disturbed than they used to be, there is, nonetheless, a process of loss, both for the child and their parents and, I would say, for the grandparents. I have personally found it inspiring to watch the courage and fortitude of Emmeline in managing her life with its new preoccupations, and also watching the tender and attentive care of her Mum and Dad in ensuring she has all she needs to keep her well. And, of course, one has to also remember those with other conditions, who are worse off, and those with Type 1 in other parts of the world who do not have the marvellous support my granddaughter has.

JDRF and other organisations and labs are doing amazing research to try to (a) prevent Type 1 and (b) treat it. They talk of developing an artificial pancreas, as the pancreas basically stops functioning with Type 1. I read yesterday of a student at the University of Huddersfield, Tyra Koslow, who has invented a blood glucose monitor for managing type 1 that can be contained within a futuristic-looking earring that resembles a tiny Bluetooth earpiece. It requires only a normal ear piercing and can pass radio waves through the earlobe to monitor the user’s blood. I am sure that during Emmeline’s lifetime there will be some amazing progress in technology.

In the meantime, those living with Type 1 will find that even if they do the same thing each day, or eat the same food, their levels are likely to be unpredictable. They vary according to weather, exercise, temperature, and stress. Hormones impact levels so there are variations when going through puberty, or, for girls, pre-menstrual or menstrual, as oestrogen levels make the body resistant to insulin. It can be difficult to control the levels perfectly, for sure, and as a child grows their body and hormones change, so managing the levels is a continuous adjustment according to their needs.

You may know people with Type 1 and not realise they have it, nor understand the demands it places on children, parents and adults to manage their health. Frank Gardner, the journalist who was disabled by a terrorist bomb, has said on television recently “what people don’t see is all the stuff that we have to deal with beneath the surface”. He describes it as the ‘iceberg’. You only see what is shown above the surface in Type 1 but below the surface there will be fingerpricks, injections, input of carbs and calculations, changes of monitor and pump sites.

Happily now there are people in the public sphere talking of their experience – ex-Prime Minister Theresa May, James Norton the actor, Sheku Kanneh-Mason, the cellist who played at Prince Harry and Meghan’s wedding, all of whom have the condition.

And so I shall be celebrating World Diabetes Day today in honour of my beautiful and courageous granddaughter, of whom I am incredibly proud. To show solidarity, on Saturday 14 November, people are being asked to wear blue nail varnish and post photos to raise awareness, so this is what I am doing!

And if any of you feel like giving any small amount to my Just Giving page for JDRF (Junior Diabetes Research Fund) then of course I shall be thrilled, as every pound or penny helps towards their fantastic research.

But either way, the main thing is to bring you some of the awareness of this condition, of which I knew nothing before Emmeline’s diagnosis in 2019.

2 responses

A tour de force about diabetes, Helen.It is worth remembering that 100 years ago the diagnosis was a death sentence, the scientific, pharmaceutical and clinical advances in management since then have been extraordinary.

Brilliant article about this difficult disease. It really makes clear how complicated it is to deal with even now in our modern age. For a child to have to cope with it, and in particular your beautiful granddaughter, must require great strength of character, but supported it sounds by wonderful parents and Granny and the wonderful NHS. Thank you .