I am re-reading Emma Sky’s excellent book The Unravelling: High Hopes and Missed Opportunities in Iraq, in which she describes her experiences as an advisor to the US army during the rebuilding of Iraq post 2003. It has brought home to me once more how important it is for leaders to take psychological and emotional responses seriously. Again and again she makes it clear that the Coalition were not thinking rigorously enough about the psychology of those with whom they needed to interact. They were missing out the human factor of emotion, family groupings, tribes, religious sects and communities. They didn’t appear to be taking into account that how people feel emotionally about events will shape their individual and group behaviours and responses.

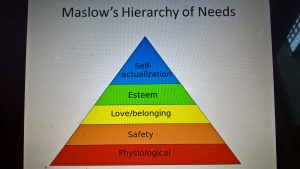

It hadn’t seemed to occur to those leading the bombardment to think ahead to how it might feel for Iraqis to have America bomb Saddam and his troops. Yes, people may well wish to be rid of a dictator, be they Saddam Hussein, Gaddafi or Assad, but it is a different matter to have a foreign force invade and then occupy their country – particularly if that occupying force have not considered safety and comfort after the event. The Coalition quickly lost the goodwill of the Iraqi people by not having had a vision of success that included stable government nor providing the people with water, electricity and supplies. It might have benefited the Coalition leaders to remember Maslow’s hierarchy of needs where he argued that if the basic physiological needs of food, water, sanitation and safety are not put in place people cannot rise up to levels of healthy communication:

Little was learnt after Iraq in the toppling of Gaddafi in Libya where the country was once again left in a state of disintegration, allowing it to become a breeding ground for the so-called Islamic State in the chaotic aftermath of that debacle. Once again in Syria one sees little evidence that the Coalition forces have stopped to consider who they are dealing with on a personality level and how best to communicate with them in the government, the Syrian people – or Putin.

Over many years working in the business world I have experienced a disparaging attitude to psychology, which they often dismiss as “psycho-babble”. I found leaders paid scant attention to the practical theories that psychology books can provide. Often the focus on people-matters is still regarded as a soft and woolly area rather than the serious ingredients of what can help leaders motivate and incentivise their staff to action.

When David and I attended a lecture last year describing a research project at Cambridge University on the subject of conspiracy theories we were shocked to hear that there was no psychologist in the team. The talk included discussion of the MMR vaccine, the supposed assassination of Princess Diana, and the idea that the US plotted 9/11. The examples contained many elements that related to the behaviours and psychology of those involved in conspiracy theories: those who instigate them, those who believe in them and those who don’t. Surely it is obvious that the belief systems of anyone involved in conspiracies would be shaping their susceptibility to either develop the conspiracy or to believe in it.

Do senior political figures read books on psychology, I ask myself? If they did I would be surprised if they would talk about others in the negative terms they often use. The egos of those in power are frequently far more sensitive than they might appear and it does make sense to stop and consider how Assad, Putin or Juncker might feel if they are referred to in a pejorative way. Talking down to this type of person might simply lead them to retaliate. The appalling rudeness that Farage, Boris Johnson and the Leave campaigners used during the Brexit campaign demonstrated all too clearly that they had not given a thought to the fact that they would inevitably need to continue to work with the members of the EU about whom they were being so derogatory. Jeremy Hunt could also learn much about how to present a case in a way that might stimulate cooperation, could he not? And how about the talented and motivated individuals who are contributing great value to our country – how might they feel when described as “foreigners”? Perhaps a read of books such as Games People Play , Where Egos Dare or Difficult Conversations might have given them some insight as to how to smooth the waters of negotiation?

Might the Coalition in Iraq have transacted differently with Maliki if they had better understood his tendencies to authoritarianism and that you can’t change people’s behaviours overnight? As it was, both General Odierno and Petraeus were wise enough to recognise that Emma Sky provided them with insights into building relationships in Iraq that they personally did not have the gifts to discover themselves.

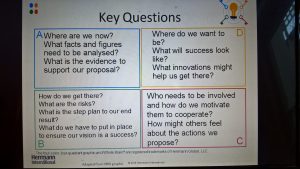

Much respect is given to the efficacy of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and yet those who govern us do not appear to have understanding of how they might themselves apply it to their leadership. If the premise of CBT is that thoughts, beliefs or expectations shape feelings and that feelings shape behaviours then the simple set of questions for an government to ask might be:

- What are we trying to achieve here?

- What does success look like?

- If this works how might those involved feel?

- If they feel like that then how might they behave?

- In taking this into account what are the risks and what is the best way to act or communicate?

- What are our priorities and what do we need to do first?

This process helps leaders include the element of emotional intelligence that seems to be missing from so much of the leadership we experience in government, business and the military. A country is made up of individuals who think and feel. The EU may seem a large bureaucracy but it is composed of individuals who have a sense of their own status and dignity. If people insult them that will have negative consequences. It seems obvious but I have witnessed many initiatives where no one is totally clear about what they are actually trying to achieve, nor how people might feel emotionally if they were to achieve it. In Iraq this seems to have been as true about the Iraqi factions as it was about the Americans. I wonder now whether the Coalition forces or the Syrian rebels have a clear vision of success for Syria? People shoot themselves in the foot by not shaping the positive outcome nor taking the emotional factor into account. Where people feel respected and included they are more likely to work collaboratively towards intended goals.

The trouble, as I see it, is that whether it is Iraq, Libya, Syria, Brexit or the NHS, no-one really seems to have worked out a clear joint vision of success or if they have it is opaque. Without this it is impossible to develop a plan. “Begin with the end in mind” is the advice in Stephen Covey’s Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, followed by “seek first to understand and then to be understood”. Both these statements relate to the right quadrants of the HBDI model below – the yellow quadrant of positive outcomes and the red quadrant of people, emotions and behaviours. Both these quadrants are, in my view, the most neglected areas of attention of leaders worldwide. As Emma Sky was aware, the world revolves on building relationships of trust and none of us can afford to forget this.

Whether it is a military operation in Iraq, the harbouring of a conspiracy theory or running an organisation, the perceptions, beliefs and emotional responses of those involved either perpetuate a problem or help solve it. Common sense, you may well say, but how often do we hear this complex but essential human factor specifically discussed in board rooms or parliament? And whilst leaders continue to discount psychology and its impact on the behaviour of those they work with, we shall surely continue to see failures of initiatives when those in charge blithely ignore how their actions might make people feel emotionally.

Some further reading suggestions:

Where Egos Dare: The Untold Truth about Narcissistic Leaders and How to Survive them by Dean McFarlin and Paul Sweeney

Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss what Matters by Bruce Patton, Douglas Stone, Sheila Heen

Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships by Eric Berne

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

Cognitive-Behavioural Coaching Techniques for Dummies by Helen Whitten

Emotional Healing for Dummies by Dr David Beales and Helen Whitten

Saneworks by Chris Welford and Jackie Sykes

Recent Comments