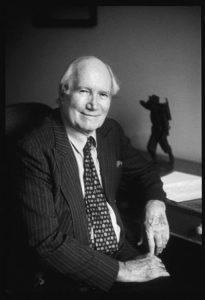

The historian Alistair Horne died on 25 May this year and would have been 92 today, 9 November. I worked for him for some six years as a researcher on The Official Biography of Harold Macmillan. I suspect we all have a teacher or boss to whom we feel grateful . For me this is Alistair. I learnt so much from watching him write and feel now that I would like to capture some memories of my time working for him.

I remember that it took me six years to move him from his old portable Olivetti typewriter to a word processor. As a long-established writer and journalist, he tapped away surprisingly fast with two fingers but eventually he did see the benefit of being able to erase errors and edit paragraphs without the necessity of Tippex or multiple attempts at retyping specific pages to fit into his manuscript.

It was probably the only thing I was able to teach Alistair. When I started working for him in 1983 the ad in The Times was for a researcher for an “established author”. Established, he was. A historian with many books to his name including the classics A Savage War of Peace, on the Algerian War, The Price of Glory, Verdun 1916, and The Siege of Paris. At the time I met him, he was busy recording the life of Harold Macmillan.

I had just begun to feel ready to take on a job that was more demanding than the freelance picture research I had been carrying out for Penguin and Macmillan. My younger son had recently started nursery and I had more time on my hands.

On reading the advertisement for Research Assistant, I wasn’t sure whether I was sufficiently qualified for the job. I discovered later that Alistair had received some forty applications, many of which mentioned degrees, which I did not.

I had worked for Macmillan publishers for many years, first as a PA to an editor, Caro Hobhouse, and it turned out to be Caro who was editing Alistair’s biography. In my time in the editorial and picture research departments, I had come across Harold Macmillan as he would come into the office about once a week and walk around talking to the staff, senior editors and Board members.

So when, many years later, in 1983, I called the number in The Times and discovered that it was Alistair Horne writing the biography of Harold Macmillan it felt a little like destiny. At the interview the coincidences continued. I discovered that I was to take over the role of a previous Research Assistant, Serena Booker, who had been tragically murdered in Thailand aged only 27. Serena was the youngest daughter of my prep-school headmaster, John Booker and his wife Peggy, and sister of Private Eye and Daily Telegraph journalist, Christopher Booker. I remembered Serena running around my school, a much-cherished little girl with blonde hair and a lively nature. These were sad shoes to step into.

As Alistair and I talked it turned out that his own daughters had gone to my senior school, Cranborne Chase. One topic of conversation slid easily into the next. I was hired.

I learned so much during that time with Alistair. How he did his research. The questions that needed to be asked. The facts and dates that needed to be checked. I travelled to libraries. I once met A J P Taylor at the Beaverbrook Library though I’m ashamed to say that I didn’t recognise him until I mentioned this dapper man in a bow tie who had been helpful in tracing some facts and my mother said, “Darling how could you not recognise A J P Taylor when you bump into him!” I had an interesting visit to Chartwell, and to Macmillan’s own home at Birch Grove. It was fascinating reading the original letters from the troops in war, and Macmillan’s own diaries.

I watched Alistair place into files the relevant newspaper articles, letters, torn-out notes for inclusion in appropriate chapters, ticking off information as it was used. I saw him sketch out his work by laying these out on his desk as he typed. He would, like many authors, rise early and go down the garden to his conservatory office, next to the mews garage in St Petersburgh Place, W.2. where he lived with his beautiful second wife, Sheelin.

I did my best to find the facts, file, archive and type accurately but I am sure I made some mistakes. I suspect there were times when I drove him mad with my other responsibilities as a wife and mother. He would often ring our home in the morning, forgetting that I had my two young sons to take to school. This was before mobile phones, otherwise I think my school run would frequently have been interrupted with his thoughts for the day.

My sons would also benefit from the snippets of research I did for some of Alistair’s articles. He wrote travel pieces for the newspapers and, as a keen skier, he described helicopter skiing in the Bugaboos including details on how to survive an avalanche. I told my sons that should they ever get caught in an avalanche they should first ‘swim’ in the snow to prevent the snow getting too compacted around them. Then, if stuck, spit in order to see which way their spit was pulled by gravity so as to identify which way to move. Hopefully they will never have to use his advice!

I also worked on Alistair’s book on the children evacuated during the war and specifically on the tragedy of the Benares, the boat that was torpedoed, where many evacuee children were drowned. During this period of research I heard of Alistair’s own experience of being evacuated to the USA and how much he had enjoyed his time there where he had made friends for life. I interviewed children, now adult, who had been evacuated within the UK, some of whom had had happy times, others terrible. I heard of the homesickness, of the difficulty recognising parents when they returned home, of how fathers tried to assert their authority on the family when they returned from the war, of mothers who had worked on the war effort and were then pushed back into the kitchen, and more.

And as for Harold Macmillan himself, I ended up with a sense of respect for his mind, his wit and humour. Of his determination to live longer when he overheard a nurse say “it won’t be long” and thought “Bugger that!” I was impressed that he continued to enjoy half a bottle of champagne every evening well into old age. The biography could not be published until after his death, and I recollect Alistair observing that despite a generous advance, when all the work was taken into account, he had earned very little over the long period it took him to complete the manuscript. Another salutary lesson for me – not to have high expectations of financial reward for writing!

After publication I could have continued to work for Alistair on future books but decided finally to do the History Degree I had wanted to do since I was 17. So, aged 39, I completed the UCCA forms and Alistair filled out the piece designed for the Headmaster. I am sure having his name on the form made a significant difference to my being accepted on interview both by King’s College London and LSE. I accepted the offer for King’s and had a mind-opening time, stimulated by amazing lecturers such as Professors Richard Overy, Conrad Russell and David Carpenter. Mind you, I suspect Alistair would not have approved of the ‘safe space monitors’ that have recently been introduced to King’s and other universities!

And so he was influential in setting me off on the next part of my career journey, as although I went into professional coaching and training I believe that this background in the themes of history and philosophy have stood me in good stead in helping clients achieve perspective.

Alistair kindly mentioned me in his autobiography But What do you Actually Do? When I wrote to him to thank him for the mention, we discovered another coincidence – that I was now living in the village of Ropley, Hampshire, where, it turned out, he had spent many childhood years! I have found that there are certain people who come and go in one’s life that seem to have had an almost destined course to cross one’s path. Alistair has been one of these. And I thought of him often as I was researching and preparing to write my own books.

He had the courage to grasp the opportunities of his era – being a spy, involved in intelligence-gathering in Palestine in World War II under Sir Maurice Oldfield, head of MI6, then working in Berlin where his cover was as a Daily Telegraph correspondent. He lived and worked in France for many years and later established The Alistair Horne Fellowship at St Antony’s College, Oxford, to support young historians. He was made a CBE in 1992 and knighted in 2003, appointed a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur in 1993 and was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. An impressive life.

For me there are many of his books on my bookshelf and many memories that continually reaffirm my love and respect for history. I feel fortunate to have known him and worked for him – I wonder, when you think back yourselves, which of your own bosses have left their mark and influence on your life?

6 responses

Wow. I loved reading this. It is like a good book that you just cannot put down until you have read it all.

You certainly hit a chord Helen. I recall a Gentlemen, Roger Gilbraith, at Xerox who was my Boss for some time. We kept in touch when he retired until he sadly passed. I think of him often and how he shaped my learning and influenced my development. Such fond memories.

Thanks Roger. Yes, it is interesting how these old influences percolate one’s daily life … for the rest of one’s life. x

I like this a lot Helen. Reading that advertisement was a tipping point in your life; Lets discuss this thing about tipping points next Weds…

Look forward to it! x

The photographs by my desk as I write are of my two newspaper bosses – Gordon McKenzie of the Daily Mail, where I had a tough training, and George Seddon of the Observer, which was more haphazard. They egged me on. My aim in life was to make them laugh. When i went freelance, George gave me his last tip. Never ask if your text is alright; it’s too easy to say, No. Instead, ask, Is that what you wanted? Because it’s easier to say,Yes.

I enjoyed reading this generous and moving tribute to Alistair Horne and how his influence filtered into your life.

I remembered generous teachers for my life in Medicine. Edgar Hope-Simpson welcomed me into his surgery when he retired and handed over to me in his Cirencester practice. Maurice Lessof for showing me the art of medicine as his first house physician and many others. Good to have old memories refreshed and remembered with gratitude.