General Sir Richard Barrons has been quoted today as saying that the UK and NATO forces are under-defended in terms of resource should Putin or others become aggressive. In addition to this there are countries within the EU who are not spending the minimum 2% of GDP required for defence, so mobilizing an effective army could be a slow process.

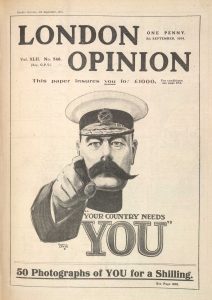

This has made me reflect on a theme that has been playing on my mind for some time: who would volunteer to protect the UK should we come under attack? In World War I, 478,893 men joined the army between 4 August and 12 September 1914. There was a sense of patriotism and duty to King and Empire fuelled by posters such as “Your Country Needs You”. In World War II 1.5 million volunteers joined the Home Guard alone.

But the UK is a very different place today. The Empire has been disbanded and our population is far more diverse. This makes me question whether there wouldn’t be some emotional conflict for some of today’s residents should there be a war and a need to defend our country from attack. After all, even people who have lived here for twenty years and taken up British citizenship might nonetheless support their original home cricket or football team rather than a British one. How might they feel about fighting for England now, should it be required?

In 1914, 1939, and even in my childhood in the 1950s, to be patriotic was something to be encouraged. Today, being patriotic is sometimes confused with being a “Little Englander”, a Brexiteer, or even a right-wing nationalist. It seems to me that this holds some dangers and does not reflect a balanced way of describing the emotional connection one has with one’s home country. After all, we have just had a visual example of this in the Olympics and Paralympics where one sees Italians, French and Brazilians waving their flags as much as we do. But would those same people choose to fight for their country today as their predecessors did at the beginning of the twentieth century I wonder? The world is far more complex.

Our history shapes our mental models and responses. Something that seems to have been little talked of in the Brexit debate is the different recent history of the other 27 EU countries compared to ours and I wonder whether this difference hasn’t, in fact, been a factor in the resulting outcome of Brexit. For we were one of the very few countries not to experience either a dictatorship, Communism, an invasion, occupation or an ideological regime in the twentieth century. Yes, we had to fight Germany to protect ourselves and our allies but we have not been invaded or occupied for centuries and have not had to live under a dominating force that limited our way of life, freedom of speech or cultural norms. In fact the twentieth century was a period that was increasingly democratic and egalitarian. Perhaps this history has had something to do with influencing the 52% of people who voted for Brexit? Perhaps our free democratic past has drawn them to have an emotional, perhaps even unconscious, distrust of Juncker’s talk of federalism?

In many of the other 27 countries thought and free speech were limited and fear was endemic within harsh regimes: Germany lived under Hitler, Spain under Franco, Italy under Mussolini, Portugal under Salazar. Bulgaria had an army coup and royal dictatorship, France was occupied by Germany, Greece had the Metaxas dictatorship and right-wing army coups, Hungary a dictatorship followed by Russian invasion. Austria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Turkey, Yugoslavia were all ruled by dictatorships and, following that, communism and the Cold War impacted many countries in Eastern Europe, limiting their ability to interact with others.

A country’s history impacts the way information is shared between generations and forms how people think. Family narratives are shaped by events. The experiences of grandparents influence the responses of their grandchildren. On our recent visit to Russia we met people whose parents still warn them to be careful of what they say. This kind of fear, a fear of reprisal for saying or doing the wrong thing limits the ability to see opportunities beyond the everyday norms. Coercion rather than persuasion is even reflected today in the words of Slovenian leader Robert Fico, currently European President, threatening the UK with punishment for its decision to leave the EU. He is waving his stick to stop other countries following suit rather than demonstrating the benefits that would hold them together.

I really wonder whether our differing past isn’t a major influence on the way the governments of Europe are responding to federalism. Perhaps it is, in some way, more comfortable to others to conceive of being ruled by a European President than it is for us, as many of them have experienced a dominant or occupying one party order previously. Whereas for us it might seem like anathema. I am, here, literally, as my blog explains, “Thinking Aloud” and I would be interested in other people’s perceptions.

But we need to learn from our past. The birth of these regimes in the twentieth century was stimulated by the global economic disaster and the 1929 Wall Street crash. Democracy was threatened as people’s livelihoods were threatened. As the economist Arthur Salter wrote in Recovery, in 1932: “The defects of the capitalist system have been increasingly robbing it of its benefits. They are now threatening its existence. A period of depression and crisis is one in which its great merit, the expansion of productive capacity under the stimulus of competitive gains, seems wasted; and its main defect, an increasing inability to utilise productive capacity fully and to distribute what it produces tolerably, is seen at its worst.” One can see this tendency mirrored today in the anti-capitalist movements and we need to beware of repeating mistakes of the past.

The severity of the 1930s economic slump directly threatened democracy and the old liberal capitalist order was replaced by state intervention. People sought strong leadership that promised relief. There was a rise in far left and far right movements, a depletion of the centre ground. In much of Europe various forms of dictatorship came to replace parliamentary systems that had become associated in people’s minds with the economic disaster, leading governments to take more responsibility for economic revival.

With the global economy today still under some threat, we need to consider how to avoid a similar experience of hard left or hard right regimes taking over. We are already witnessing this, both in the UK and in Europe. In Germany’s recent election the AfD and communist parties both did well. Whilst capitalism has its faults it has, nonetheless, provided millions of people with work and income. If we keep knocking the extraordinarily good – in historic terms – lifestyle we have in the UK we jeopardise its future. Life will never be completely equal – we all have differing gifts and cannot legislate for perfect parenting – but if you read Johan Norber’s new book Progress (OneWorld Publications, 2016), you will find statistics to demonstrate that we are witnessing the greatest improvement in global living standards ever, with malnutrition, illiteracy, poverty, child labour and infant mortality falling faster than ever before.

There is still more to do but we need to balance the critical analysis with appreciation of what we have in this country. It isn’t perfect but actually it is still a very good place to live in comparison to many other countries. The fact that so many people want to enter and live in the UK is surely evidence that we are the envy of much of the world. Our problems are mirrored elsewhere. After all, if you look at what is happening in the rest of Europe we are no worse in general attitude to others. We are currently the fall guy of Europe for expressing the concerns that many others are experiencing. Our general tendency to apologise for everything we do won’t help us negotiate our new place in the world. Despite Brexit, despite the problems, can we not take pride in our institutions of government, law and industry that support democratic stability?

Is not regard for one’s country and its history natural and to be encouraged in order to protect the values and freedoms that we have fought for and developed over so many centuries? The difference in my own rights and lifestyle as a woman to those of women elsewhere is tangible. Can we not feel patriotic without being accused of being a small-minded Little Englander? A work team can be proud of their company but have trade partnerships with others; a family can have an emotional bond but still be open to friends. Pride in our country does not prevent us being open to relationships with the world.

In this increasingly complex world, if we were under threat how many of us would find it in ourselves to stand up and fight for our country’s way of life should the need arise? I wonder…

3 responses

Thanks. Good ‘thinking aloud’ that touches on many themes that point to a need for share values – including patriotism – with a collective will to preserve them.

As well as the potential for divided loyalties that you mention we will be helped as a nation when there is a more equable distribution of wealth and opportunity.

When estimations suggest that 1% of the population share as much wealth as 20% of the whole and there is a growing two tier system provision, within health and education, we are a divided nation.

One can see, as you write, the consequences, mirrored today in the anti-capitalist movements, that are growing.

We need the citizenship of the UK to feel part of a whole nation committed to shared values that include equity of opportunity, as at least an aim, and the patriotism that follows.

It may illusory to regard the past as simpler than the present. By definition the past is history and the end of the story is known and can therefore be easily grasped. In the present one has to imagine likely outcomes and make judgements considering the influence of multiple variables on the process that we might be viewing. It is worth recalling that the social milieu pre WW1 was turmoil with major industrial unrest, extreme concern over Ireland and of course the “women’s” movement that had degenerated into near terrorism. To the average Edwardian life may have seemed complex. Similarly prior to WW2 there was the general strike, real fears of a communist revolution, the profound financial and then economic depression and of course the side issue of the Oxford Union vote to not fight for King and Country. Before being aware of the darker side of fascism the attraction of Hitler compared to communism was understandable. I think if the external threat is perceived as great enough, patriotism will appear.

‘Despite Brexit..’.?