“A reader lives a thousand lives. Someone who doesn’t read only lives one.” George R.R. Martin

I was saddened to hear in a radio discussion last week that approximately 40% of prisoners are functionally illiterate. I was shocked that this reflects an educational system that must have been incapable, over many different governments and decades, to enable pupils to leave school able to read. If one takes the message of the quotation above, this leaves each of those individuals with only one life rather than with the possibility of living many different lives. It leaves them stuck, often in a background with few advantages, without the ability to perceive the options available to them to start a different way of living. We are letting them down.

Prisoners who can’t read are unlikely to get a job. If they don’t find work it is 90% more likely that they will re-offend, which is likely to cause harm to those against whom he or she re-offends, represents a personal loss of freedom, and is a huge cost to the taxpayer. Reading is a key that opens up opportunity.

So this got me thinking about reading and whose responsibility it is to raise the level of literacy. Of course reading is taught in school and is the business of government and the Department of Education but it also needs to be encouraged in the home. It is the responsibility of all those raising a child – teachers, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles – to encourage and help that child to master this essential life skill.

It isn’t always easy to motivate a child to read but in my experience the earlier one makes it a part of daily life the more easily it becomes a habit. I have always been a bookworm, as was my mother. From an early age I have lost myself in magical worlds, adventures, and ideas. I feel I have lived in different countries, taking on the lives of the characters I was reading about, whether in Russia, Africa, Peru or on another planet. Each new chapter opened my mind to new ways of life and perceptions beyond those I had been taught at school.

It is easy for any of us to get out of the reading habit. When I was busy with small children I didn’t find the time to read as frequently, although I was re-reading my childhood books to my sons and now read to my grandchildren. I am also thrilled to see my six-year-old granddaughter wolfing her way through book after book since she learnt to read.

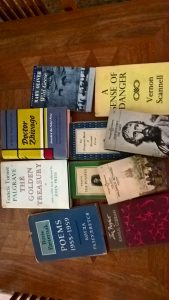

I am delighted to have more time now, as a grandmother, to return to reading. This has made me reflect on the fact that so many of the books we read, both classics and contemporary, that influence our minds and our lives, are read before we have even begun to live life ourselves. I look at the books on my shelf, which I feel tell the story of my identity, and realize that I read many of these as a teenager, at a time when I knew nothing of the many experiences of which the authors were writing. And yet their ideas broadened my mind and helped me develop knowledge and understanding that I may not have achieved without them.

For me the Russian writers have been, I think, my greatest influence, writing as they did in the context of a historic or political setting and yet bringing events down to individual human experience of love, family relationships and friendships. Sadly I can’t express myself as well as a Tolstoy or Pasternak!

At school we are generally given a reading list and I was interested to see that Andrew Halls, the Head teacher at King’s College School, Wimbledon, has recently developed a specific reading list for his pupils that he believes can develop empathy in the boys, beyond what they experience in their digital games such as Minecraft or ninja turtles. He has chosen books he considers to have complex characters who are leading believable lives. “From their interactions and choices,” he said “children can learn to understand and interpret people’s motives and feelings”. Agree with his choices or not, I suspect that we can all relate to having read something that made us cry or made us angry, even though we knew the character was fictional. This affinity we feel for a character expands our insight into other people’s lives and can develop not only empathy but also compassion and can help form the values we embrace as we grow up.

I hope that this simple but essential skill of reading continues to be taken seriously in schools and institutions. We are better informed of the kind of difficulties children have in learning to read, such as dyslexia – in my schooldays children were just regarded as dim which was a terrible restriction to the opportunities available to them. Thankfully today dyslexia is better understood although even now I am aware that it can be difficult to get a child tested early enough to catch them before they lose confidence or interest. I am glad that Richard Branson has recently been promoting the fact that he has been thoroughly successful despite his dyslexia.

So, as I choose now, as we move house, which books must stay by my side, I am also selecting which books I shall read again now that I am mature and have lived more of life. I share with you a poem, Anthology, I wrote about the poems and books that have influenced my life. Perhaps this will stimulate your own reflection on which books you wish to keep by your side, possibly to read again.

Who’s that knocking?

The poets. And I, the listener,

open the door of my memory

to the sense of a book in my small hand,

the delight of being ill, off school,

a mild ailment, tucking myself in, under the cover.

I recollect the yellowing paper, a dry touch to my finger,

the smell of the pages sucking me in,

allowing me to lose myself,

spin scenes from the words.

Who’s that knocking?

It started with Walter de la Mare.

What’s that buzzing in my ears?

Jack Clemo’s Christ in the Clay-Pit

that opened my eyes to the sacred.

The fading inscription from my parents

in The Golden Treasury that sits on my shelf,

a gift on my confirmation, aged fourteen.

The thumbed pages that flap open

to Byron, Lawrence, Wordsworth, Yeats.

Happy those early days when I read

but had not experienced the touch of a lover,

the pain of a parting with silence and tears.

I scour the pages now and ask, where was Blake?

Who’s that knocking on the window,

pushing it open to consider the night,

to look at the stars, look at the skies?

Pascal, whose Pensées let in the light

to previously shuttered views of perception.

My father’s gift, three shillings and sixpence.

Pascal’s universe “an infinite sphere,

the centre of which is everywhere,

the circumference nowhere”

blowing my mind,

forcing me to reflect on infinity, on man with or without God.

About suffering he was not wrong.

Who’s that pricking at my conscience?

The dusty blue book some fifty years old

still read, Pasternak, hammering always

the need for the heart of the matter,

the quest for a way, fame not a pretty sight,

success not your aim.

He the one who set my pen rolling

to emulate his words, his life,

with my teenage poetry,

still shapes my words and views,

whispers in my ear not to be an empty name

to defend my position, to be alive, myself.

Who’s that crying?

I saw my infant son die a few weeks after he was born,

Charles Lamb’s cradle-coffin verse of doom perverse beside me.

I shattered the cosiness of family life with divorce,

yet the stars have not dealt me the worst they could do.

I have travelled among unknown men,

visited fifty countries or more, through heat and dust,

through ice and Arctic Circle; Yevtushenko’s Russia,

Leopardi’s Italy, Goethe’s Germany,

and walked with Gibran in the Lebanon,

sat with Mary Oliver enjoying the sharpness of the morning

in New England. Seen that poets must loiter in green lanes.

Who’s that knocking on the door?

The chattering of the beat poets

howling their way through the entrance in the garden wall,

while I hide beside the hollyhocks

with the Romantics at my side.

I re-read my early poems in their schoolgirl script,

interspersed with Vernon Scannell’s notes in the margin,

laugh and cry with Copus and Cope,

leave Motion untouched in the bookcase,

switch off McGough on a Sunday afternoon,

and wonder which poet will next direct my hand,

enflame my heart.

One Response

Thanks for highlighting the need to promote and encourage reading and the delight and self development that often follows.absorption in a well chosen book.

In one study of young offenders 50% showed dyslexic traits that had not been assessed in schools.

Without and screening and creating an educational program for these disadvantaged children society will pay the cost in social disruption and expensive incarceration..